|

Greater Atlanta by Mark Steinmetz.

|

Photographs by Mark Steinmetz

Nazraeli Press, CA, USA, 2020. 88 pp., 73 illustrations, 10½x12".

Absorb more poetry.

It’s neither a belated New Year’s resolution nor an item on my to-do list, it’s a mental reminder to feed my soul and beam it outward to others. In our world of swiping, liking, texting, emoji exchange, and other forms of quick contact through partitions and pixels, absorb more poetry is one antidote. The keyword being absorb. Take things in, soak them up. Let one’s pores fill like a sponge until they are heavy, a reassuring kind of heavy, like a weighted blanket.

This year I am absorbing the poetry of Georgia Blanche Douglas Camp, an African-American poet and playwright born in 1880 in Atlanta, Georgia. I began on January 1 with Camp’s 1918 poem, “The Heart of a Woman”:

The heart of a woman goes forth with the dawn,As a lone bird, soft winging, so restlessly on,Afar o'er life's turrets and vales does it roamIn the wake of those echoes the heart calls home.The heart of a woman falls back with the night,And enters some alien cage in its plight,And tries to forget it has dreamed of the starsWhile it breaks, breaks, breaks on the sheltering bars.

These beautiful and intense words reverberate when I receive Mark Steinmetz’ photobook Greater Atlanta, brought on by the cover photograph. I languish in its shadows and light. The black-and-white image, Barrow County, GA, 1994, shows a young black girl looking over her left shoulder, directly into Steinmetz’ lens. Dressed in a striped shirt, standing in a parking lot at night. Her expression is complicated, multi-layered, and magnetic. Just as Camp deliberately chose and arranged language for its meaning, sound, and cadence, so too does Steinmetz in this image, and the 72 that follow, all made between 1992 and 2008.

|

The book, a newly remastered edition of the 2009 Nazraeli Press publication, is part of a trilogy called “South”, the first of which, South Central, was published in 2007. According to Nazraeli, the format, sequence, and design mirror the original printings — including Linh Dinh’s poem “Recent Archeo News” — but the materials have been improved with a sumptuous cloth cover and matt fine art paper.

After several armchair visits to Greater Atlanta, similarities in themes between Steinmetz’ images and Camp’s words intensify, each making my skin prickle and tingle at different registers. There is seclusion, solitude, pain, love, the role and costs of living — for it is a role each of us pays to play — compassion, yearning, and progress.

It starts with love. The first image inside the book is a close-up view of a car, the upper windshield and part of the roof, upon which is a drawn outline of a love heart. It is daytime, sunny; the car is stationary, the road in the background devoid of action or objects. Steinmetz winks at this little ideograph. We are going on a journey of tenderness it whispers, winking back. But like all great love stories and all great poems, the trip will be unpredictable, touching, and traumatic. The twists of the girl’s hair in the cover image resound again. I buckle my imaginary seatbelt.

Initially what stands out are recurring subjects and photographic behaviors: asphalt, transport, windows, overgrowth, darkness, animals, contours, branches, hands, bricks, scars, offcuts, and highlights. Then I change gears for a Sunday drive through the pages. I’m looking at actions and feelings. Penetration, protection, and departure. A stand-off between two broken trees. A brother with his long arm draped around his younger sibling. A flock of ducks, almost in a line, waddling away from Steinmetz. I’m looking at sound and sensation. Two chattering cherubs of a weather-worn statue, their stone hearts warmed by a splinter of sunlight. The rustle of a brown paper bag in the crook of an arm. The pressing of vinyl when you slide into your favorite booth at your favorite diner. It is a book of visual particulars displayed as emotions that swing less like a pendulum and more like petals tossed during a game of she loves me, she loves me not, Greater Atlanta loves me, it loves me not…

After several armchair visits to Greater Atlanta, similarities in themes between Steinmetz’ images and Camp’s words intensify, each making my skin prickle and tingle at different registers. There is seclusion, solitude, pain, love, the role and costs of living — for it is a role each of us pays to play — compassion, yearning, and progress.

It starts with love. The first image inside the book is a close-up view of a car, the upper windshield and part of the roof, upon which is a drawn outline of a love heart. It is daytime, sunny; the car is stationary, the road in the background devoid of action or objects. Steinmetz winks at this little ideograph. We are going on a journey of tenderness it whispers, winking back. But like all great love stories and all great poems, the trip will be unpredictable, touching, and traumatic. The twists of the girl’s hair in the cover image resound again. I buckle my imaginary seatbelt.

Initially what stands out are recurring subjects and photographic behaviors: asphalt, transport, windows, overgrowth, darkness, animals, contours, branches, hands, bricks, scars, offcuts, and highlights. Then I change gears for a Sunday drive through the pages. I’m looking at actions and feelings. Penetration, protection, and departure. A stand-off between two broken trees. A brother with his long arm draped around his younger sibling. A flock of ducks, almost in a line, waddling away from Steinmetz. I’m looking at sound and sensation. Two chattering cherubs of a weather-worn statue, their stone hearts warmed by a splinter of sunlight. The rustle of a brown paper bag in the crook of an arm. The pressing of vinyl when you slide into your favorite booth at your favorite diner. It is a book of visual particulars displayed as emotions that swing less like a pendulum and more like petals tossed during a game of she loves me, she loves me not, Greater Atlanta loves me, it loves me not…

|

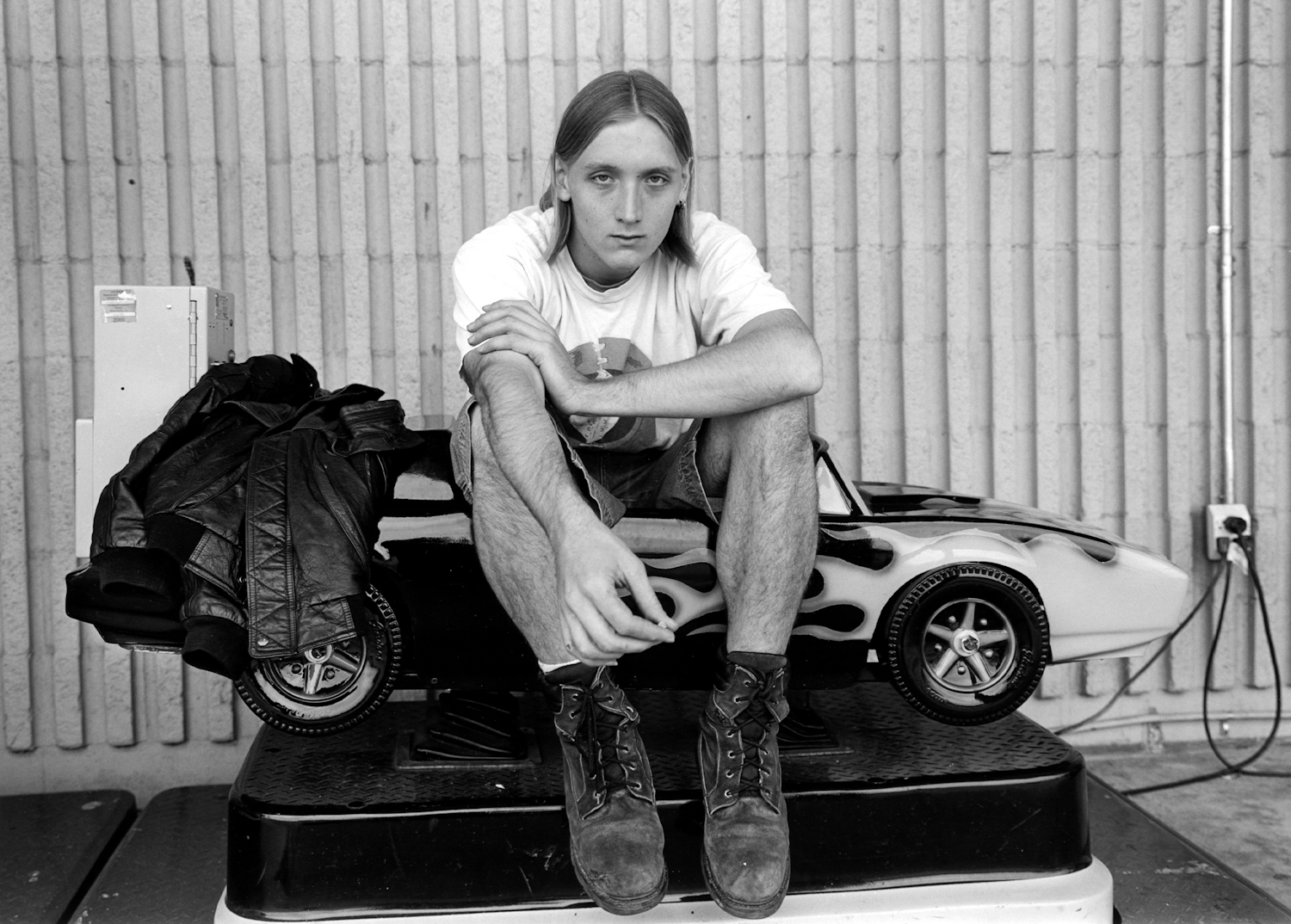

What I am most absorbed by are the facial expressions. Most mouths are closed. Most eyes focus on a specific something — a newspaper, another face, a cigarette, an ATM — or nothing at all. There are few smiles, fewer frowns. Each portrait vibrates, a hum of the age apathy. In the image of two young black girls striding through a parking lot in front of a coin laundry, I hear Camp’s “Calling Dreams”:

The right to make my dreams come true,I ask, nay, I demand of life;Nor shall fate's deadly contrabandImpede my steps, nor countermand;Too long my heart against the ground Has beat the dusty years around;And now at length I rise! I wake!And stride into the morning break!

There is a photograph around the halfway mark, intentionally placed I hope, at which I pull over. It is taken from inside Steinmetz’ car looking out the window to the other side of the highway, heavy with traffic. But Steinmetz also includes his rear vision mirror and the steady stream leaving the city with him. This is the ‘Greater’, a sort of middle ground between committing to a lifelong relationship with the urban whirr or its deceptively simpler peripheries.

|

I love a photobook with extra legroom. There is no superfluous design here. The white space is liberal, and the sequencing is cool and smooth. Its elegance gives way to the images.

The journey ends with a 3x4” photograph, Steinmetz looking skyward at a squirrel running along a powerline, as if headed back to the book’s beginning. The connection is palpable, the day-active creature scurrying back to see the night-active girl on the book’s cover. Squirrels are an adaptive and resilient species because they are under constant threat; from people, other animals, and the ever-changing environment around them. Perhaps the people and places Steinmetz introduces us to.

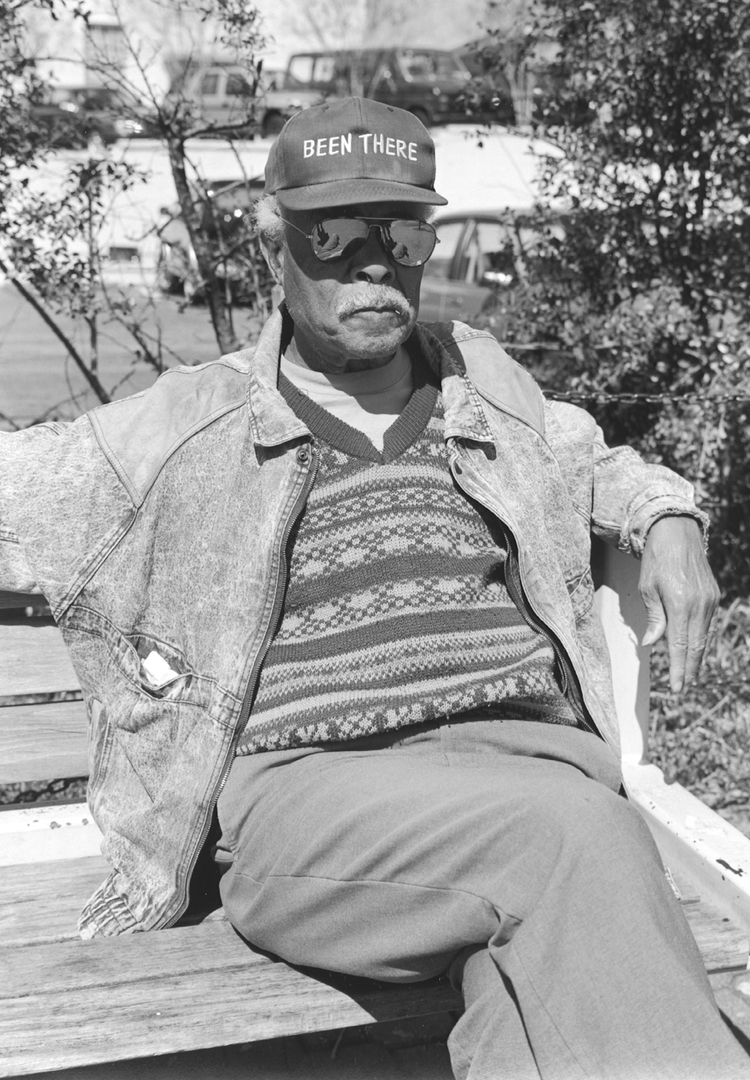

The core common denominator, though, is the absence of time. Whether I’m absorbing Camp’s poetry or Steinmetz’ photographs, time doesn’t fly by or slip away. There is no time. There is no “Junior” wearing his cap backwards, sitting outside on a step, taking a break to read Women’s Physique World. There is no concrete sidewalk etched crudely with ANN, ANNA, ANNIE ANA ANNE. There is no abandoned Ruscha-esque gasoline station nuzzled in fog. No man resting on a bench wearing mirrored sunglasses and a hat emblazoned with BEEN THERE.

There is no time, only place, Greater Atlanta. Thanks to Steinmetz I have been there. A place to be absorbed in and by, a place of visual poetry through Steinmetz’ patient and watchful eyes, and a place of community, passing, oppression, affection, and wild imagination.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

The journey ends with a 3x4” photograph, Steinmetz looking skyward at a squirrel running along a powerline, as if headed back to the book’s beginning. The connection is palpable, the day-active creature scurrying back to see the night-active girl on the book’s cover. Squirrels are an adaptive and resilient species because they are under constant threat; from people, other animals, and the ever-changing environment around them. Perhaps the people and places Steinmetz introduces us to.

The core common denominator, though, is the absence of time. Whether I’m absorbing Camp’s poetry or Steinmetz’ photographs, time doesn’t fly by or slip away. There is no time. There is no “Junior” wearing his cap backwards, sitting outside on a step, taking a break to read Women’s Physique World. There is no concrete sidewalk etched crudely with ANN, ANNA, ANNIE ANA ANNE. There is no abandoned Ruscha-esque gasoline station nuzzled in fog. No man resting on a bench wearing mirrored sunglasses and a hat emblazoned with BEEN THERE.

There is no time, only place, Greater Atlanta. Thanks to Steinmetz I have been there. A place to be absorbed in and by, a place of visual poetry through Steinmetz’ patient and watchful eyes, and a place of community, passing, oppression, affection, and wild imagination.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|