|

This Earthen Door. By Amanda Marchand & Leah Sobsey.

|

By Amanda Marchand & Leah Sobsey

Datz Press, Seoul, Korea, 2024. 128 pp., 8¼x10½".

Amanda Marchand’s and Leah Sobsey’s This Earthen Door is a creation of stunning beauty and reverence — reverence for Emily Dickinson and her love of flowers and poetry, and, more generally, reverence for the natural world.

Using digital scans from a facsimile edition of Dickinson’s mid-19th century herbarium, the original too fragile to be taken from dark storage at Harvard’s Houghton Library, their imaginative reinterpretation of this work is a collaborative synergy of photography, poetry, art, botany and bookmaking.

There are many ways to approach This Earthen Door: as an inventive engagement with Dickinson’s own 66-page herbarium; as an immensely original artists book; as an introduction to the Victorian pastime of botanical pressings; as a reevaluation and further resurrection of the feminine in early photography; and, most assuredly, as pure visual pleasure — but all the while noting the underpinnings of conceptual depth and breadth that carry Marchand’s and Sobsey’s effort into another realm.

Considering This Earthen Door through the lens of ecofeminism (“a view of the world that respects organic processes, holistic connections and the merits of intuition and collaboration”*), one sees the deep connections between Amanda Marchand’s and Leah Sobsey’s three year immersion into the world of Emily Dickinson’s herbarium with the alchemy of plant emulsions, collaborative research and practice.

|

Asked about the spark that led to This Earthen Door, Marchand and Sobsey said they had long wanted to collaborate on a feminist project, and in their discussions during the Covid pandemic, together arrived on Emily Dickinson’s herbarium. With a background in literature, Marchand said she was interested in bringing the literary world, specifically poetry, into her artwork. Sobsey, on the other hand, has had a long and rich history working with archives, and this Dickinson archive seemed a natural choice for her.

Referencing mid-19th century photography, Marchand and Sobsey used the historic anthotype process of applying plant-based extracts to paper and then exposing that paper to sunlight with a photographic negative on top. The resulting images, while beautiful, are fugitive, and after being scanned for prints and reproduction, are now also kept in the dark.

|

With self-imposed rules and structure, detailed notes and charts, and partnering with experts in both botany and Dickinson herbarium studies, Marchand’s and Sobsey’s methodology and documentation mirrored Dickinson’s own rigor of method, which had elevated her herbarium to scientific research, botany, affording one of the few avenues of scientific study open to American Victorian women.

Determined to stay as close to the flowers in Dickinson’s botanical work as possible, they chose 66 specimens of the over 400 in the original herbarium, one for each of Dickinson’s 66 pages.

Marchand and Sobsey grew most of their own flowers and plants or collected them on walks just as the poet did, choosing plants in Dickinson’s herbarium that were crossovers to their own gardens in Quebec and North Carolina. It was those flowers that provided the plant-based emulsions used in the anthotypes and chromotaxia, their color taxonomy.

|

|

This Earthen Door is a gorgeous book whose every element is considered for beauty and knowledge. Upon opening the book’s cover, the reader encounters 13 separate and brilliantly colored pages washed with plant pigment emulsions, ready-for-exposure. Younghea Kim, Datz designer, and Sangyon Joo, Director, suggested putting each color sheet on its own unique paper stock whose somewhat raspy and unforgettable tactility is carried in finger memory as one reaches the smooth interior pages. Even as I type this, I remember the surprise of the papers’ textures on my fingertips.

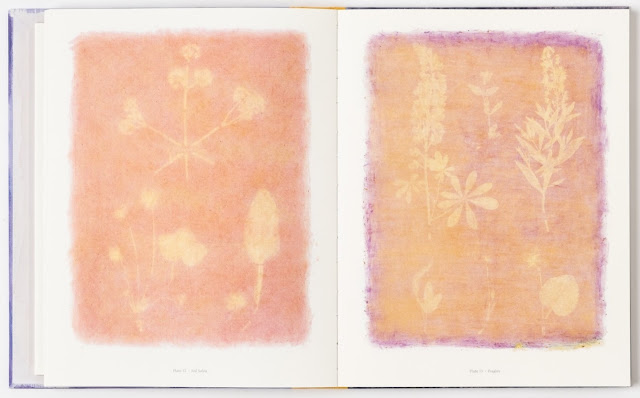

Following the full color pages are the 66 stunning color plates of the anthotype interpretations of Dickinson’s herbarium, some of which bear notations in Dickinson’s own hand. To say they are vibrant and alive and seductive is to understate their impact. The plates not only carry the reproductions of flowers but are themselves composed of organic matter.

Literally bookending the plates, eleven additional full color pages appear at the back, adding to one’s retinal memory long after the cover is closed.

|

Inserted within This Earthen Door is another pleasure, Bloom – is Result, a second smaller booklet generously sharing process information, the anthotype timing chart, a color wheel and the description of additional work done during the Datz Museum of Art residency. As one more gift to the reader, there is a small piece of handmade paper embedded with wildflower seeds to plant with Dickinson’s poem, ‘To make a prairie’.

The Korean translations interspersed throughout speak both to Emily Dickinson’s international following and respect for Hangul, the beautifully graphic writing system of the publisher’s home country.

Ghost Flowers, an essay by Dickinson scholar, Marta Werner, underscores the poetry of time travel in this conversation between Amanda Marchand, Leah Sobsey. “Are they images of the herbarium’s lost memories of the vernal earth of more than a century ago? Or are they after-images from the herbarium’s dream of a world to come. . .”

|

|

Throughout much of human history, women have carried the herbal knowledge of a culture or community, and despite being denied access into most of academe and scientific societies, brilliant and intrepid Victorian women found ways to research and practice in scientific fields, eventually gaining the acknowledgment and respect of their colleagues.

Marchand and Sobsey, in their research and investigations, came upon Mary Somerville, a Scottish polymath for whom the designation ‘scientist’ was created. There is some dispute as to whether she or her colleague John Herschel was the first to discover the use of vegetable matter in creating photographs through the anthotype process, but there is no doubt that she was part of the flourishing and exciting early discoveries within photography during themid-19th century. At the same time, Anna Atkins, having learned the cyanotype process from Herschel made her celebrated seaweed photograms and is the first person to publish a book with photographic images. Although Atkins, Somerville, and Herschel were contemporaries of Dickinson, it’s unknown whether she knew of their work, but she, too, through the study of botany made her way into scientific exploration.

|

As creative descendants of Atkins and Somerville, Amanda Marchand and Leah Sobsey are of the lineage of women artists working with nature and photography in an alchemical vein, and it’s more than fitting that their ravishing book is inspired by and pays homage to the proto-ecofeminist Emily Dickinson.

Purchase Book

*Britannica

|

|

|