|

Anonymous Objects. By Kim Beil.

|

Inscrutable Photographs and the Unknown

By Kim Beil

SPBH Editions, 2023. 175 pp., 4x6".

"It’s easier to ignore things we do

not understand than it is to try to

capture and comprehend them.

This perceptual strategy may even

be an evolutionary necessity."

— Kim Beil, Anonymous Objects

inscrutable /in-skru-tə -bəl/: not readily investigated, interpreted or understood: mysterious

Photography is an extremely deceptive medium, but given its ubiquity, I think we are blind to most of what it offers. I am not sure how to calculate the number of photographs I see every day, but I reckon it’s in the thousands. For most people, I am afraid, the constant barrage of pictures we all experience allows us to think we understand what we see in photographs. Because of its accessibility, we’ve become complacent (or perhaps numb?), and too infrequently question our relationship to photography, readily assuming what we see is what we get. Unfortunately, it’s a bit more complicated. Every picture is full of ideas, intentions, circumstances, and objects we know nothing about. Part of the draw of photography is its ability to offer clear depictions of time and space, but I'm of the belief that the unknowable parts of a photograph are its most interesting and essential attributes. I think those of us weaned on darkroom photography can speak to that first, magical experience when we watched an image emerge in a tray of developer. Every day, despite how inundated I am with photographic information, I try to remember the fundamental mysteriousness that first drew me to the medium.

|

The new book by Kim Beil, Anonymous Objects, asks the reader to embrace and relish the mysteries of photography by taking note of the little, often unknowable, items that appear within its frames. The book is the fifth installment in the SPBH Essays series and is seemingly about the small objects that appear in photographs that we know nothing about, often just little things that fall outside the scope of our own experience. What do these objects represent if we don’t know what they are? Does that change how we understand a photograph? If we can’t identify an object depicted in a picture, what does it represent? Can we really know a picture if we can’t understand all that is held within it? When I got into photography, the first artist I really studied was Frederick Sommer, and as a result, I remain committed to the belief that the best photographs represent ideas beyond what is described in their frames (Sommer’s doll head is more Enochian than documentary). This is important, I think, when reading Anonymous Objects, because on the surface Beil is writing about specific attributes — those tiny things stacked out of the way on the top left shelf in Walker Evan’s photograph of a general store in the American South — but digging deeper between the lines, Beil is really creating an incredible labyrinth of ideas about what photographs can and cannot represent, like Sommer giving something well beyond a literal reading.

|

As many before her, Beil’s argument pays homage to Roland Barthes, his name and ideas appearing throughout her text:

“Photographs of unrecognizableIt had been a while since I read Camera Lucida, Barthes’s groundbreaking book on photography that questioned the very nature of the medium, and I found that revisiting it can shed some light on Anonymous Objects. First published in 1980, Camera Lucida is a personal narrative in which Barthes developed a free-form, stream-of-conscious text divided into small, discrete parts, each section its own meditation on photography. Throughout Camera Lucida, Barthes negotiates sophisticated ideas about pictures, language, symbolism, and representation, ultimately offering new conclusions about photographic images, and their infinite capacity to evoke personal experiences and cultural representations.

things produce a curious analog

to this ‘temporal hallucination’

that Barthes finds in portraits.

Studying inscrutable photographs,

we come face to face with our

own limits, just as Barthes faces

his own mortality when studying

a picture of a person.”

|

|

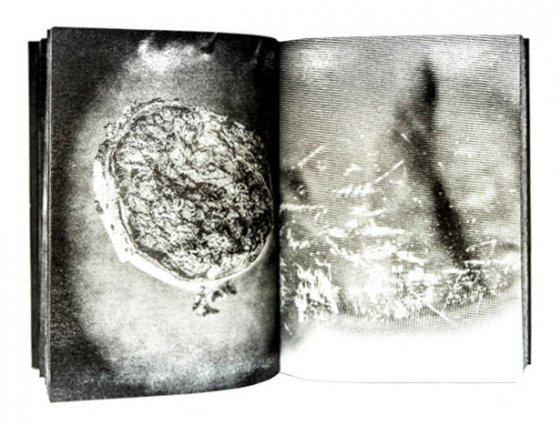

Beil’s Anonymous Objects offers something similar, a free-flowing text that breaks down the personal and cultural significance of photographs. Using the small, unknowable attributes of different pictures, Beil negotiates much more complex ideas about representation, time, and both personal and cultural symbolism. Part of what I love about Anonymous Objects is quite simple: how the text appears on the page; the design of the book dictates its meaning. Throughout the book, Beil dissects several different photographs, some iconic — like Alexander Gardner’s portraits of Lewis Payne before his execution and early souvenir photographs of George Washington’s home — as well as pictures collected from flea markets. As she deciphers these pictures, Beil knits together a larger narrative about the objects that appear in the photographs and how they impact our understandings. The design of the book, however, facilitates more poetic possibilities. Printed in a big, bold font that allows single sentences to fill an entire page, her phrases and ideas breakdown in an evocative manner, each encapsulating a distinct and succinctly described idea of its own (in sharing quotes from the book, I’ve transcribed them like they appear on the page, as though poetry not prose). You can read the book cover to cover to follow that larger train, but you can also open the book at random and find brief but mysterious ideas about photography. This approach replicates something I love about the medium itself — full of short, sharp, and clear ideas that somehow remain elusive and mysterious, presenting clear and wonderful ideas but also an unending array of ambiguity and questions.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

Brian Arnold is a photographer, writer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY. He has taught and exhibited his work around the world and published books, including A History of Photography in Indonesia, with Oxford University Press, Cornell University, Amsterdam University, and Afterhours Books. Brian is a two-time MacDowell Fellow and in 2014 received a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Institute for Indonesian Studies.