|

Outside the Frame

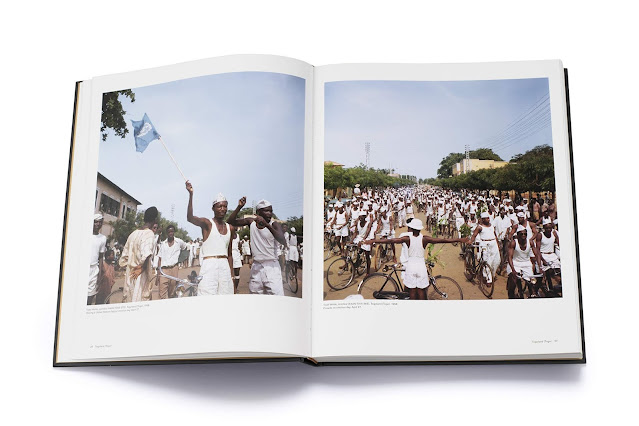

Thames & Hudson, London, UK., 2021. 256 pp., 10x12".

In 1958, mid-century street photographer Todd Webb (1905-2000) was commissioned by the United Nations to document “the progress of industry and technology" in what were then eight different African nations, either recently independent or about to become so. Thames & Hudson has now released a large selection of the resulting works in Todd Webb in Africa: Outside the Frame, edited by Aimée Bessire and Erin Hyde Nolan.

It is an admittedly hefty book, measuring 10” x 12”, but its size allows us to take in fully the quality of Webb’s images, blown up almost full to the page. Included are a handful of black-and-white images, but the book is mostly composed of full-color photographs. Off the bat, the book is interesting for this fact alone, as Webb rarely ventured outside his preferred medium of black-and-white. The publication is doubly exciting because these images were never exhibited within Webb’s lifetime, beyond a short brochure from the UN: the full archive was only recently recovered in a collector’s basement, nearly sixty years after its creation.

|

|

© 2021 Todd Webb Archive

|

The accompanying texts, however, are where the book truly shines. Its eleven contributors include writers, historians, photographers, and artists, all of whom hail from the countries depicted, or at the very least are scholars working within these regions. Together, they investigate at every turn the motivations and limitations of Webb’s perspective — namely, that of a white American traveling through Africa on behalf of the United Nations. They go “outside the frame” to raise questions about visualizing postcolonial Africa, namely its complex sociopolitical matrix of power relations, racial dynamics, imperialism, and industry.

|

|

© 2021 Todd Webb Archive

Todd Webb, Untitled (44UN-7916-069), Togoland (Togo), 1958. Loading people and goods at Lomé harbor. |

Attempt, of course, is the keyword here: we must also recognize that Webb’s UN assignment was made to visualize Africa as “modern” only in the sense those in the global North would consider it so. And Webb, while leery of exoticizing Africa, was not fully beyond romanticizing the continent. He wrote that Southern Rhodesia was too close to American life to be true “African,” whereas by contrast “Togo and Tanganyika are the best Africa so far.” The “best” Africa was something defined vaguely as feeling not too modern — rather ironic, given the terms of his assignment.

His narrative of “progress” can also be sharply bittersweet in retrospect. Examining Webb’s sunlit images of mining camps and power plants in Southern Rhodesia, Gary Van Wyk explains that 1958 was the halfway point through the Federation’s uneasy existence. He cannot read these images without a sense of foreboding: “I know what is coming. The Bush War. But first the Federation will fail.” He sees with apprehension, knowing what is to come and what has passed — the rising political tension, the coming civil war, and the Mugabe regime.

Through their own intimate knowledge of these places, the authors also easily see what is not pictured. For instance, there are no images of Nyasaland, also part of the Federation, as its natural beauty was at odds with the industrial views needed for Webb’s assignment. Indeed, of the few landscapes in the book, most feature images of extraction and waste, or shipping yards and docks within sparkling blue waters. Hyde Nolan observes that Webb’s reverence for natural landscapes, inherited from his teacher Ansel Adams, sits uneasily alongside unseen histories of displacement, ecological disturbance, and grueling labor. Between the monochrome of vast topographies and mechanized technologies, there is little space for the human element. “The possibility of one world,” as Van Wyk writes, “entails the expulsion of the other.”

|

|

© 2021 Todd Webb Archive

|

Emphasizing such tensions does not detract from Webb’s images, but rather enlivens them further. Webb’s portraits of various individuals he met are particularly fascinating in this regard. In her essay, Rehema Chachage notes how Webb’s image of a Tanganyika policeman, standing under the sun with a phone to his ear, feels distinctly awkward. His smile is slightly confused, his grip on the phone tense. But the gap between photographer and subject makes for an extraordinarily gripping image, perhaps more so than if they had been fully at ease with this strange American photographer.

|

|

© 2021 Todd Webb Archive

Todd Webb, Untitled (44UN-7930-609), Trust Territory of Somaliland (Somalia), 1958. Two women walking on the beach, with a dog to their right. |

What makes the archive so fascinating for these contributors is also what made the UN rather uninterested in the majority of Webb’s work. These images contain complex ambiguity, reflecting locals’ own questions and uncertainty about the future. From Webb’s staggering 170 rolls of film, only twenty-two were published in a short seven-page brochure, “United Nations Photos, Supplement No. 7,” with these vibrant color negatives flatly printed in black and white.

The new anthology finally does justice to the depth of Webb’s images. From the perspective of Africans looking at a non-African looking at Africans, these seemingly straightforward documentary images are imbued with new insights and nuance. Todd Webb in Africa is a powerful contribution to a growing body of visual scholarship that underscores how a photograph always, always, exceeds its intention.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

All images Courtesy of Thames & Hudson.

InHae Yap is a researcher whose work explores shared themes, questions, and histories between photography and anthropology. Her writing has appeared in photo-eye, Strange Fire Collective, and Critical Interventions, among other publications. She is currently based in New York.

|

| Todd Webb in Africa: Outside the Frame |

|

| Todd Webb in Africa: Outside the Frame |

InHae Yap is a researcher whose work explores shared themes, questions, and histories between photography and anthropology. Her writing has appeared in photo-eye, Strange Fire Collective, and Critical Interventions, among other publications. She is currently based in New York.