|

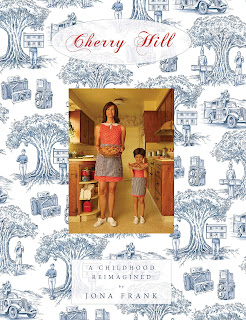

Cherry Hill. By Jona Frank.

|

Photographs by Jona Frank and Rick Schatzberg

I can’t help but imagine the photographers Jona Frank and Rick Schatzberg as neighbors. Frank grew up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and Schatzberg on Long Island. Both were bedroom communities of major cities, Philadelphia and New York respectively. Both were suburbs built in the postwar boom. Both promised success and security, but enforced social conformity. Both Frank and Schatzberg found an emptiness there, yet a plenitude in memory. They weren’t neighbors then, but they are now, on my bookshelf. Reading their photo memoirs, I felt as if I was triangulating between them. I could see my own suburban hometown hovering just north of them on the map.

The best memoirs encourage this kind of identification and creative geography. Reading about someone else’s life inspires reflection on one’s own, no matter how distant they might be in time or space. In some ways, photographs are more emphatically first-person than any written text. We see through the photographer’s eyes, without the reframing or obfuscation of memory. Frank’s Cherry Hill: A Childhood Reimagined and Schatzberg’s The Boys combine text and image, playing on the rich associations of photography with truth and memory to tell personal histories.

|

Frank opens with a classic film sequence: a close-up of a telephone on olive green wallpaper, then a long shot of a young girl laying upside down on a teal couch. Then the surprise: an inverted photograph of a woman in a kitchen. This is a point-of-view shot, uncorrected. We are seeing through the little girl’s eyes. Cherry Hill is the story of Frank’s childhood told in written passages and elaborately staged photographs. Frank cast her friend Laura Dern as her mother and three different actors play Frank at different ages of her childhood.

Frank writes emphasis in all caps. Her narrative is colloquial, like a note passed to a friend: “Every night, and I mean EVERY night, we ate dinner at 5:30 pm.” The most resonant, familiar passages come early, before the drama of Frank’s inner life is replaced by the dramatic turn in her family’s life. She recalls her art teacher’s frustration when she preferred to dream images onto a blank sheet of paper, rather than draw. This early memory is beautifully mirrored by her later discovery of photography, that medium in which images do appear, dreamlike, on white paper.

Frank’s sequencing is often a story of its own. It continues past the end of the narration or it zooms in, leaving little Jona suddenly alone on a white page. Like a graphic novel, the story is told on multiple levels, the pacing controlled by page-turns and placement. The typographic choices also evoke the world of comics. Sometimes words float on their own, other times they caption images cheekily, as when Frank’s father tells her she could grow up to be either a nun (turn page) or a nurse (turn page). Both borrow costumes from central casting.

|

Even in memoir, the character of the self must be shaped. But, it’s by revealing one’s inconsistencies and failures that make readers trust the memoirist. Like watching a character in a horror movie enter a dark basement, I longed to cry out to Frank: Yes, you can go to college, no matter what your mother says! You must leave Cherry Hill!

|

The Boys. By Rick Schatzberg.

|

Joking around, partying, drinking and doing recreational drugs is nominally what brought them together. As one of the boys says: “We had some of our most meaningful early psychedelic experiences in the shade of those trees. There was a rope that hung down from one of the trees and we used to swing over one of the small streams. We were getting to know each other stripped down to the bare bones.”

And that is how they appear, literally stripped down in Schatzberg’s portraits. Several of the men appear shirtless. Surgical scars, sunspots, and sagging skin make their life histories visible. The book’s accordion-folded pages afford a comparison between the cool, objective light of the present portraits with the warm and grainy snapshots of the seventies. Often I struggled to see the similarities: a Casio watch, the shape of a nose or eyebrows. Difference is what Schatzberg sees in his friends, too. He writes: “Time’s unfolding is obvious: balder, grayer, folds and wrinkles, scars. There is an eternal present in a photograph, but I see past, present, and future all at once. Something recognizable, beyond resemblance. Brain scientists and Buddhists say there’s no essence or persisting self, only memories and character traits that infer continuity.”

|

Things left unsaid, petty grudges and annoyances, loom in Schatzberg’s memories. In recollecting conversations with his friends, he points to the things left out. These negative spaces in dialogue give shape to Schatzberg’s character. There are some things that are too hard to say, like details that are obscured in a photograph. For me, the punctum of the text lies in these absences. Schatzberg relays an encounter with his ailing father, who admitted to feeling as if he had lived a charmed life and that his cancer diagnosis seemed impossible. Schatzberg didn’t respond in the moment. But this book, which becomes increasingly a story of life and loss, is his response.

Memories acquire new shapes as we replay them in our minds. Even when aided by photographs, retelling these stories to ourselves changes them. Memory adapts with the changing sense of self. Both of these photographers’ books highlight such changes in perspective, which makes them more true to the experience of memory and, thus, more affecting than any objective picture would allow.

Purchase Cherry Hill: A Childhood Reimagined

Purchase The Boys

|

|

Read More Book Reviews