|

Street Portraits. By Dawoud Bey.

|

Photographs by Dawoud Bey

Mack, London, UK, 2021. 144 pp., 9½x11¼".

Dawoud Bey is having a moment. It sure took a while — he’s nearing 70, with a stack of prestigious fellowships under the belt — but the wait was worth it. Bey’s sprawling retrospective An American Project opened recently at the Whitney in New York. It features several dozen prints, spread across multiple floors, encompassing his entire career, now stretching into its sixth decade. Technically this is the show’s second stop since it opened at SFMoMA last year. But alas, COVID. SFMoMA was shut down for most of 2020. So for practical purposes, the Whitney exhibition is An American Project’s public debut, a chance to hit reset and start over in New York, not far from Bey’s childhood in Queens.

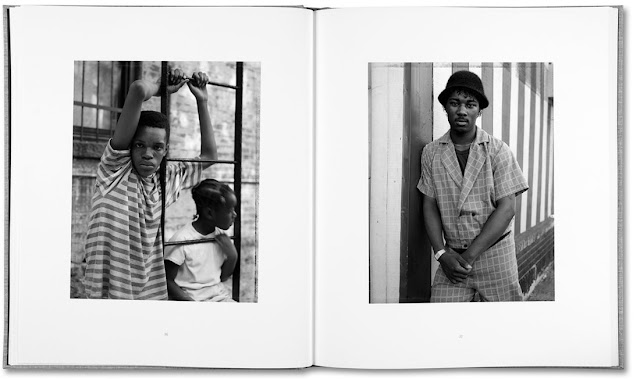

The pandemic reset may have been serendipitous, since it allowed the current show to open nearly concurrently with Dawoud Bey’s new Mack book, Street Portraits. The monograph may be brand new but the photos aren’t. Bey shot them between 1988 and 1991 — the supposedly “kinder and gentler” Bush years — mostly in Brooklyn, using a view camera with Polaroid 55 film. Visitors to the Whitney can see a handful of prints from the series tucked into one room, where they comprise a small part of An American Project. For the book, the selection has been expanded to include seventy photos. In just about every way — from observation to exposure to tonality to reproduction — the pictures are spectacular.

|

As the title implies, this series has the loose, providential quality of street photographs. Bey encountered his subjects in passing. There was no studio, no lighting, no prelude or courtship. There was simply May I take your portrait?, a quick snap, and then the next photo op. “The challenge of photographing in the street is to make it feel like the most natural thing,” says Bey, “even though it clearly isn’t.” His exposures have the improvisatory freshness one might expect from a fleeting process, but also something else. They manage to sample just about all of humanity. There are old and young, men and women, wealthy and poor, singles and couples, lovers and misanthropes. Some are dressed in suits. Others in terry cloth. There’s an albino, an athlete, a biker, a street worker, churchgoers and hip-hoppers. Comparisons to Sander’s People of the Twentieth Century may be inevitable, and the standard of skill is similar. But Bey is less concerned with vocational identity than human connection.

There is also the important fact that all of his subjects are Black, as is Bey. Street Portraits is not so much a collection of pictures as it is a communal portrait of African-American life in a late 20th-century city. “History is the thing that I’m mostly preoccupied with,” he says. “How can one imagine and visualize African American history, make that history resonate?” He’s created an invaluable record. Street Portraits could slot as easily into a sociological museum as the Whitney.

Greg Tate’s afterward places Bey into historic context, musing on the particulars of Black life and its photographic depiction. “Bey’s portraits,” he writes, “celebrate Blackfolk’s uncommon carriage, forged under multigenerational pressure.” Borrowing Cornell West’s phrase postural semantics, Tate explains “we show up ready for the world adorned and armored with our mean lids, and even meaner leans.” Perhaps one might read the bold stance of a girl with school medals as a mean lean. Or the immense chapeau of a woman on Fulton and Washington as a mean lid. Other photographs resist poetic phrasing, but they exude a similar penetrating quality. A woman sitting by her daughter stares up at Bey’s lens with all of her might. A couple clutching near a road offers Bey their full attention before resuming their embrace.

|

Such images feel relaxed and natural, a million miles from the depictions of Black America which commonly circulated at the time: magazine photos of troubled thugs with weapons, crossed limbs, and saggy waistlines. Even the pictures of Janette Beckman and Jamel Shabazz, made in the same era with some sensitivity, strike a false note in comparison to Bey. They are too performative and artificial, offering a selective view of Black culture. Of course, all photography is selective and Bey’s pictures are no exception. But somehow he’s managed to broaden the net. His pictures seem an unfiltered sample of Black life — the “uncommon chosen people”, to use Greg Tate’s phrase — in 90s Brooklyn (a few photos are included from Rochester and DC).

The racial component of Street Portraits cannot be overlooked. But the book goes beyond that, and it’s worth noting Bey’s skill as a portraitist. His ability to connect with strangers and defuse their guard is uncanny. Without fail, every person in these photos looks directly at Bey’s camera. “Blackfolk’s eye-to-eye looking back game can meet any righteous or even reckless eyeballing judgement the world might bring,” writes Tate. You’ll find no cheesy mugging for the camera here. Perhaps those exposures have been excised? Or were never created? In any case, the frames selected are vulnerable and honest.

The choice of Polaroid Type 55 is adroit. The process created both a negative and positive, meaning that he could keep a record of each image, while offering a a print to his subjects. Perhaps they still circulate in some quarters, in family albums or on refrigerators? As for the negatives, their inky intensity and rich tones seem tailored for Black and Brown skin. Meanwhile, the brighter tones drift off into blank reverie. Bey’s use of a view camera to create sharply contoured edges fronting bokehed backdrops brings his characters into relief, against familiar scenes of chainlink, porches, and sidewalks. Add in developing stains along the edges and the total effect is brilliant. These people from forty years ago appear animated and alive. Yet they cannot escape their photographic artifacts, trapped in alchemical ether like lightning in a bottle. All of the above has been superbly captured in book form by Mack, as is their custom. Cover, paper stock, tonality, and design are top-notch. It may have taken forty years for these pictures to surface in book form, but it was worth the wait.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.