|

Please Notify the Sun by Stephen Gill.

|

Photographs by Stephen Gill

Nobody Books, 2020. 168 pp., 111 color illustrations, 8½x10¾".

Odette fish, Mother’s Day, May 16, ‘81.

Mom’s cursive handwriting in blue biro on the back of a color snapshot. I am cradling my first fish, caught on a crude rod of sorts, a 1970s glass Coke bottle with yards of line wrapped around its base. It’s a Murray River carp, an invasive mud-loving species which cannot legally be returned to the water alive. Pop made the photograph, which explains the framing; he was notorious for cutting off heads with his camera. Moments later, my first fish is also headless thanks to dad’s knife and tossed into the air for our cats to fight over.

Firsts are big in life, and especially in amateur photography. First child, first birthday, first car, first kiss, and first graduation. Their uniqueness and how we save and protect them via photography, memory, and orality ensures they last. In Snapshot Versions of Everyday Life (Popular Press, 2008) Richard Chalfen writes: “There are good reasons why people take more pictures of their children when they are very young than when they are older, why parents take more pictures of their first born than later children, why family albums contain more pictures related to births than deaths, to achievements rather than defeats or disappointments”.

The basis of Stephen Gill’s latest photobook Please Notify the Sun marks a similar first: to catch a fish and photograph it from the inside out. And here’s the first of many catches: Gill must catch said fish. No popping to the shops to buy the catch-of-the-day, no shortcuts. A task easier said than done, especially when you start mentally working your way through the equipment, determination, patience, and hearty helping of good luck required. Oh, and that Gill takes it on during the Covid-19 pandemic and knowing that he is, in his own words, “really unskilled at fishing”.

According to Nobody Books, the publishing imprint Gill established in 2005 to market and sell his photobooks, he made nine trips and spent thirty hours before finally landing his catch, helped by his daughters Ada and Ylva to whom Gill dedicates the book. The date was April 10, 2020 at 17:32, which Gill texted to his friend and neighbor Karl Ove Knausgår – who wrote the accompanying essay – with these details: Sea Trout, 2.4 kg/62 cm, coordinates 55.5004 Latitude / 14.3289 Longitude. Over the next ten weeks, Gill photographed his sea trout every day using a specialized camera, microscope, and lighting.

There’s a lot to take in here; many questions form before getting to the fish pictures. Mostly though I think about the experiences of a father and his children on a quest to catch a fish. The planning, the excitement. The rugging-up needed to withstand the cold weather, evidenced by the black and white photographs of Ada and Ylva that bookend the story. The waiting, oh the waiting. The conversations, the transfer of familial knowledge, the many questions a father might pose to pass the time including, “What do you think the inside of a fish looks like?” More waiting, snacking, looking for sticks. The inevitable reassurance: Better-luck-next-time. The chin-scratching, the big breathy sighs into the air. Was that a bite, a nibble? Did you see that, that, THAT! That flick of silver…? Going to bed, staring at the ceiling asking: Lucky trip number 7, 8, 9?

|

I think too about the inclusion of scientific data in Gill’s text message to Knausgår. The exact location of where the fish was caught, its species, weight, and length. These function like a photograph, a record that has utility, authority, and classification. A record of life and death.

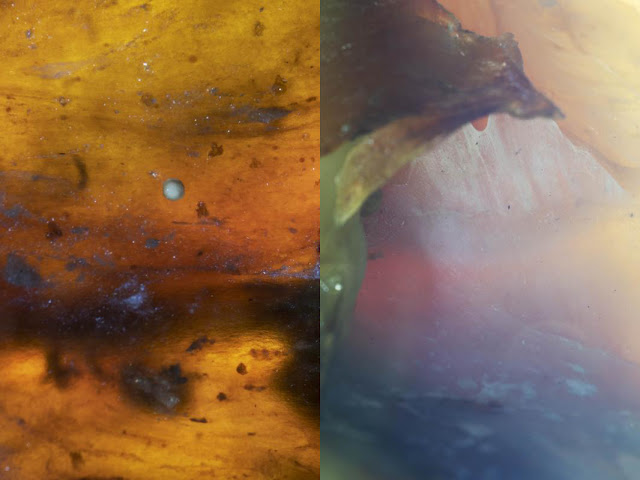

Before turning the pages, I ask my daughter Hepburn what she thinks the inside of a fish looks like. “Blurry, lots of red spots, lots of other dots, maybe some different colors too, like some big cans of paint fell on the ground”. She’s right. There are more than 100 color images, all the same size, of the inside of Gill’s sea trout. The only sequencing rule that stands out is a loose following of the principles and elements of design: line, shape, color, form, texture, space, and contrast. Some sections look redder than others, some more cavernous. Hepburn and I spend an afternoon sharing what we see in each image: a landscape, blood vessels, flower petals, shark’s teeth, a sheep’s heart, coral, lava, a tongue, stars, honey, a volcano, Mars, scars, termite mounds, mud puddles, ice, the moon, coffee, tinsel, an upside-down shadow, granite, a lychee, mold, dust, the Titanic, Jell-O, glue, a spider’s web… and on we go. Anything but the inside of a fish. And yet, the images look exactly how we imagine them to look. Not one thing or another. Everything and nothing.

|

Marvin Heiferman, in his excellent book Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe (Aperture / UMBC, 2019) points out: “Even today, researchers and clinicians need to be trained to not only look carefully at what they anticipate seeing, but also to scan for unexpected data or relationships that might, upon reflection, turn out to be of significance.” This helps to convey one of the many aspects that make Gill’s images compelling: they ask the viewer to carefully observe the layers within, the assortment of crannies and crevices despite their inherent flatness. Granted this can be a challenge with abstract photography, but I borrow from the author Lyle Rexer to note that with Gill’s images we are looking at both a visible reality and a suggestion of reality. There is what we see, what we perceive, as well as our emotional response and interpretation.

As with most of Gill’s photobook offerings, Please Notify the Sun is handsomely constructed and printed, forming part of a themed trilogy with The Pillar and Night Procession. A tighter edit of fifty images would have worked equally well. The supplementary saddle-stitch booklet with Knausgår’s essay The Spirit of Place is delightful, with its sun-colored cover and murky-water-colored pages.

The recurrent after-image that stays with me is the first one after the title page, where the sea trout’s eye meets mine. A hello and a goodbye, an exchange of death and life, of still and moving. It continues to haunt me, though now accompanied by the American rock band Soundgarden’s song Black Hole Sun. I can’t switch it off. The band’s lead singer Chris Cornell once said in an interview: “A black hole is a billion times larger than a sun, it’s a void, a giant circle of nothing, and then you have the sun, the giver of all life. It was this combination of bright and dark, this sense of hope and underlying moodiness.”

Indeed: a fish’s eye is no match for the size and weight of our sun, yet its power lies in how much it can see through its rounded cornea. It offers an almost 360-degree field of view, unlike we humans, who are limited to about half that amount. I imagine Gill staring longingly into this black hole, diving in headfirst with hope. In doing so Gill reveals the lights and darks, the shapes and shadows of all that neither we nor the sun can appreciate without his childlike inquisitiveness, his great love of picture-making, and his unrelenting belief in the power and wisdom of the photographic unseen.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

Odette England is an artist and writer; an Assistant Professor and Artist-in-Residence at Amherst College in Massachusetts; and a resident artist of the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Studio Program in New York. Her work has shown in more than 90 solo, two-person, and group exhibitions worldwide. England’s first edited volume Keeper of the Hearth was published by Schilt Publishing (2020), with a foreword by Charlotte Cotton. Radius Books will publish her second book Past Paper // Present Marks in collaboration with the artist Jennifer Garza-Cuen in spring 2021 including essays by Susan Bright, David Campany, and Nicholas Muellner.