|

Terminus by John Divola.

|

Photographs by John Divola

Mack, London, UK, 2021. 68 pp., 24x31½".

Black Circle 1924, by the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, is an oil-on-canvas of a perfect black circle on a white background. It is approximately 42 x 42 inches, and held in the collection of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. According to the author Stephen Farthing it is one of 1,001 paintings you must see before you die. Though Malevich returned to representational painting, his fetish for content-free forms influenced the growth of abstract art in the Soviet Union and Western Europe. He is not the only artist to indulge in black circular shapes: Wassily Kandinsky, Jiro Yoshihara, Lyubov Popova, John Latham and others have also been seduced by their dark curves and contours.

Circles are omnipresent, from nature and religion to cartography, astronomy, architecture and money. Many studies offer evidence and theories for our attraction to them. Eye-tracking studies, perception evaluations, reviews of children’s drawings, and analyses of typography. In The Book of Circles: Visualizing Spheres of Knowledge, designer Manuel Lima provides a wealth of examples that nature is not the only justification for our love of all things round. He writes, “the copious layers of cultural meaning we have added to the circle through the ages are ultimately grounded in an instinctive evolutionary proclivity. As with many other areas of human aesthetics, the circle’s inescapable beauty seems deeply rooted in our biology.”

|

John Divola would understand. For six years, he has created his own layers of cultural meaning through the deliberate gesture of spray-painting circular marks and then photographing them in the high desert town of Victorville, California, about 50 miles east of his home. An “unremarkable scrub desert” that is “still pretty isolated” Divola describes during a recent interview. Here, he found his version of inescapable beauty: the George Airforce Base, abandoned since 1992. Though the airfield is still operational, the square mile of derelict buildings offer provocative spaces for “quasi-criminals”, like Divola, to intervene, resulting in the singular work Terminus. The cover of which depicts a perfect black circle.

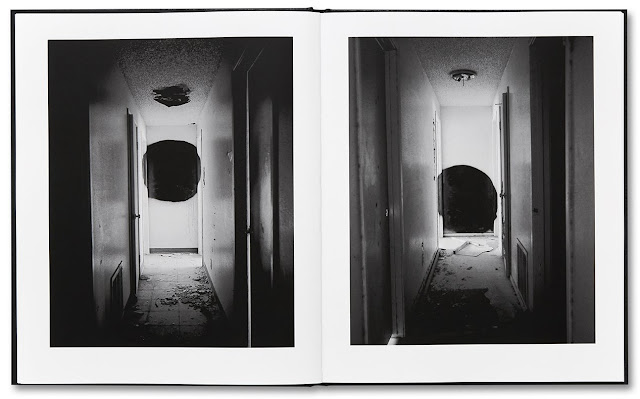

That word ‘intervene’ gives pause in context of Terminus. It has many synonyms — interfere, mediate, intercede, interpose, affect — but its most basic meaning refers to a happening in space or time between two things. In Divola’s case, there are many such happenings: An artist and his desires, paint and rigid surfaces, a camera and available light. Each communing in different hallways, which Divola says he “got really interested in”. I can see why. A hallway is a sort of intervention in architecture, its primary role a transition space, usually with speed and efficiency in mind. It creates a sense of anticipation. It is likened to the first paragraph of a novel, luring the audience into continuing the journey until the end. This latter association feels at home with Terminus; you can’t start this book without committing to the final scene.

There are several reasons for this. Divola’s photographs are on the one hand straightforward: dark primarily circular shapes painted on walls at the ends of dilapidated rectangular hallways, photographed frontally and formally. Yet intellectually and psychologically they are complex, further heightened by the book’s sequencing. As a viewer, I begin at the opposite end of one of these hallways. I look at a dark circular shape, it looks back. We acknowledge each other. Am I spectator or participant? Have I entered a theatre where hallway ends are Divola’s stages for amusement? With each page turn, the shapes begin to morph. They become larger, wider, oozier, looser. The doors coming off the hallways, offering escape routes, multiply and then recede. The floor detritus including dust, planks of wood, flaked plaster, fiberboard also fluctuates. And then The Shape — at some point it becomes a singular proper noun in my mind — starts to move. I swear at times it levitates, leaks, and glows. It swells over the doorframes, as if wanting to hold the fort. I forget it is ‘just’ a blob on a wall because I have assigned it personality, verve, and menace. Like a mirage or that proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, I can’t ever get close enough.

|

As with Malevich, Divola was driven by “a desire to be as reductive as possible”. In Divola’s case, through the interplay of photography, sculpture, painting, performance, and installation. I find these photographs anything but reductive. Their location and interventional technique are specific, yet their meaning and purpose abstract and amorphous. The Shape could be read in many ways — as a void, hole, mark, gap, or symbol. The anonymity and nebulous nature of The Shape offers its own vocabulary. It is a metaphor, compositional tactic, and character. We do not need text to tell us what it is or stands for. The Shape is the strong and silent type. It is the writing on the wall.

I am reminded of one of Wallace Stevens’ best-known poems Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Not just for his reference to circles in stanza ten — When the blackbird flew out of sight / It marked the edge / Of one of many circles — but for a correlation I see between Stevens’ and Divola’s ideas on perspectivism. Perspectivism is the notion that looking at and evaluating a situation or artwork from different points of view is crucial. Terminus offers the reader exactly that.

I can’t divulge how Terminus ends without ruining the experience. I will say there are good reasons for its title. We can’t maneuver our way through any kind of space without coming to a conclusion. The narrowness of the hallways, the capricious offerings of light, the acuity of where Divola stood. Of how our bodies and memories immerse into interior spaces. These are some of the intoxicating after-effects of Terminus.

Divola’s images deliver more than representations of imperfect dark blobs painted onto damaged walls. They highlight the role of gesture in communication and cognition. From those who designed and built the George Airforce Base, to interventionists, like Divola, who make contact with its surfaces. Terminus is a deft overlapping of time, meaning, and function, and invites us to consider gesture as a unique kind of speech mark in space.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

Odette England is an artist and writer; an Assistant Professor and Artist-in-Residence at Amherst College in Massachusetts; and a resident artist of the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Studio Program in New York. Her work has shown in more than 90 solo, two-person, and group exhibitions worldwide. England’s first edited volume Keeper of the Hearth was published by Schilt Publishing (2020), with a foreword by Charlotte Cotton. Radius Books will publish her second book Past Paper // Present Marks in collaboration with the artist Jennifer Garza-Cuen in spring 2021 including essays by Susan Bright, David Campany, and Nicholas Muellner.