Speaking for myself, the conceptual and emotional urgency with which I pursue my photography can get in the way. I sometimes forget that a simple walk with a camera, a willingness to see the world with fresh curiosity and a love of the materials of photography are the only things you really need to make pictures full of insight, poetry, beauty and joy. My first viewing of the new Jamie Hawkesworth book, The British Isles, was a lovely reminder that a photographer needn’t be overburdened a critical or social agenda and armed only with an affection for life and an acute sensitivity to light and color, one can still make important and insightful photographs.

The book is over 300 pages. The only text appears on the title page and the colophon, the rest is full of rich, colorful pictures. There is no explanation about when and how the pictures were made, except that they were all made in the British Isles between 2007-2020. I must confess, I had to look up what exactly constitutes the British Isles (short of the larger islands) and learned that it is an archipelago composed of over some 600 islands, including Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Hebrides. I must also confess that I know little about Hawkesworth, short of what I pulled from Wikipedia, and thus, I relished the opportunity to come to these pictures totally blind and without expectation.

|

Hawkesworth’s sense of color is amazing. The pictures are rich with warm tones, often with a distinct yellow base note (primarily because he loves late afternoon light). I don’t know if these pictures were captured digitally or with film, but I would venture a guess that at least some of them come from film; Hawkesworth seems to use slightly underexposed images quite successfully on occasion, exploring rich and dark color palettes and gradients. A lush, yellow light with deep shadows appears time and again throughout the book, something I delight in every time.

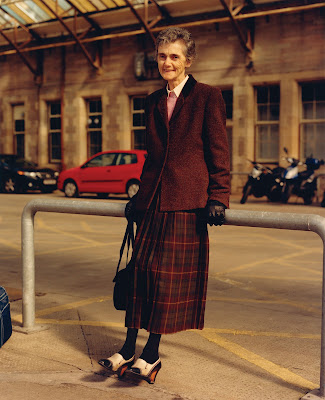

Without any overtly didactic or political stance, Hawkesworth does offer the viewer a reasoned perspective on life in the British Isles. The pictures are mostly of people, depicted simply and affectionately, with a keen eye for the social elements that define contemporary life. Muslim boys and Catholic students, shopkeepers and holiday seekers, rich and poor; Hawkesworth strives to document a complete social spectrum. The best comparison I can come up with is August Sander. Like Sanders, Hawkesworth offers an incredible cross-section of the social geography of his time. While the motivation and methodology are different, Hawkesworth reveals the British Isles as a dynamic, multifaceted region, full of people of many colors, nationalities and classes, each an essential piece of a national identity. He celebrates racial and social and diversity, and in a way that feels genuine and celebratory; all of his subjects are photographed with respect, affection and, at times, even with delightful humor. The bulk of the book is composed of portraits, but the inclusion of landscapes – iconic coastlines, torn fences and partial loaves of bread – provides a lovely context, suggesting a cultural persona grounded in something that proceeds the corporate takeover of globalization, something distinctly of the region.

|

There is one thing I’d like to change about this book. There are only three monochrome pictures, all of Muslim youth. I like the pictures, and they add an important demographic to his survey, but just three black and white photographs feel like an afterthought, too deliberate of an attempt at inclusion. And because of this the pictures seem more conspicuous, and the kids depicted less apart of the whole.

I’ve gone through the book several times, and each time I come back to the same word or idea, joy. I do have a clearer understanding of Hawkesworth’s objectives, to affectionately detail the people and things – in all their humility – that define life in the British Isles. Nevertheless, what I love about Hawkesworth’s pictures is all the joy they exude, a joy for simply being in the world, for the pure phenomenon of being as we are and in the places we call home. They are also about an incredible joy for photography, a joy found in paying close attention to light, color and the simple shape of things. Looking through The British Isles made me want to do one of the first things I did with photography – go for a long walk with lots of film, and full of genuine openness to be in the world, and to see what simple pleasures and insights await around the next corner.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

Brian Arnold is a photographer and writer based in Ithaca, NY, where he works as an Indonesian language translator for the Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University. He has published two books on photography, Alternate Processes in Photography: Technique, History, and Creative Potential (Oxford University Press, 2017) and Identity Crisis: Reflections on Public and Private and Life in Contemporary Javanese Photography (Afterhours Books/Johnson Museum of Art, 2017). Brian has two more books due for release in 2021, A History of Photography in Indonesia: Essays on Photography from the Colonial Era to the Digital Age (Afterhours Books) and From Out of Darkness (Catfish Books).