|

Zone Eleven. By Ansel Adams & Mike Mandel.

|

Photographs by Ansel Adams

Edited by Mike Mandel

Damiani, 2021. 112 pp., 83 illustrations, 11x9".

Ansel Adams needs no introduction. He remains the most famous photographer of the 20th Century nearly four decades after his death. His images saturate popular culture through calendars, posters, and books, all buffeted by keen marketing. They circulate also in the photo community, although perhaps to a lesser degree. Iconic shots like Moon Over Hernandez, Monolith, and Tetons And Snake River helped to define the f/64 aesthetic, crystalizing the majesty of the west, and influencing a generation of tripod-toting acolytes. Adams’ legacy extends beyond images to methodology. His three books of technique, The Camera, The Negative, and The Print set the standard for analogue processes, their notoriety outstripping any books of his actual photos. And the ten-grade zone system Adams developed to calibrate his own monochrome exposures remains widely influential, albeit a bit musty at the edges.

It’s this zone system that lends its name to the latest Ansel Adams book. But unlike his other monographs, this one was not authored by Adams. It’s by the wily jack-of-all-things-photo Mike Mandel, who selected the pictures from Adams’ archive. He was given free access to Adams’ back catalog, housed primarily at CCP in Tucson and the CMP in Riverside, pouring over more than 50,000 pictures. His title Zone Eleven signals an extension of the master’s oeuvre (with a knowing wink to Spinal Tap), reaching just one more notch beyond previous efforts. Mandel’s findings indeed expand the Adams territory, but they probe more sideways than beyond. His targets were not the epic Adams landscapes of popular consciousness. Instead, Mandel concentrated on side gigs and professional jobs shot by Adams for commercial clients or universities. The bread and butter assignments on which he made his living as an up-and-coming photographer.

|

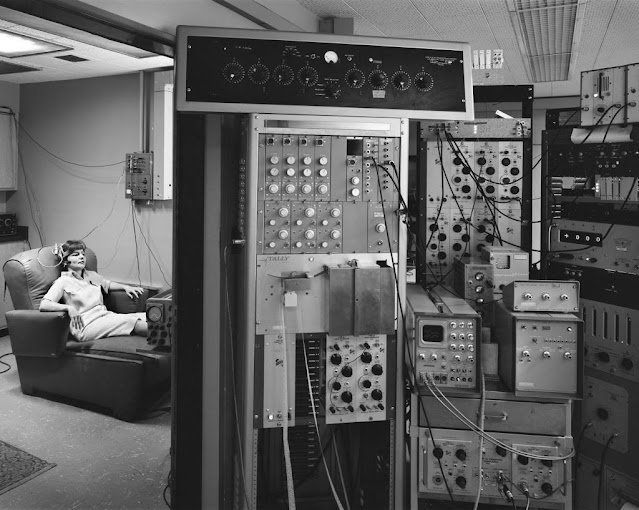

As it turns out, there were scads of these lesser-known pictures. The book highlights 83 (a nod to The Americans?). If they seem out of character for Adams, perhaps his popular persona was equally fabricated. The essential point of Zone Eleven — and the galvanizing force for much of Mandel’s career — is that the interpretation of individual images is malleable, and easily subjugated by curation. Mandel drives this point home from the book’s get-go, with a series of poolside photographs showing divers caught mid-air. Shot by Ansel Adams, these photos bear no obvious connection to Yosemite or waterfalls, or any of his popular work. The same judgment applies to succeeding pages, with pictures of sunbathers, mountaineers, shops, industry, and a couple kissing on their doorstep (Cole and Dorothy Weston!). There are movie theaters, plate-glass displays, stage actors, war prisoners, a pinhole photo, and a picture with post-Friedlander layering. In general, there’s a lot of human activity, passing through a variety of styles, none particularly concerned with the zone system or f/64 or previsualization. This is not the Adams we thought we knew, but it’s him nonetheless. A list of annotated captions in the back confirms their provenance.

For Mandel, reconsideration is a routine habit. His landmark book Evidence (co-authored with Larry Sultan) set the standard for scrambled expectations in 1977. While Evidence sourced incredible photographs from reams of menial scientific and corporate literature, Zone Eleven reverses track, pulling banal moments from a celebrated oeuvre. Damiani describes Zone Eleven as a “a companion book to Evidence,” and it’s hard to argue. The monographs are comparably sized, with similar typeface, title placement, and cover design. The spines are eerily identical. It’s here that Mandel clarifies his collaborative intent, crediting the late Adams as co-creator. The dual-authored spine is the spitting image of Evidence, and the take-home lesson is the same in both books: context drives meaning. In Damiani’s words, “as Evidence reframes the institutional documentary photograph with new context and meaning, Zone Eleven responds to the audience expectation of ‘the iconic Ansel Adams nature photograph.’”

All well and good. But how are the pictures in Zone Eleven? If they’re not as strong as the ones in Evidence, that’s forgivable. Few photographs anywhere can stand up to the work in that book. Unsurprisingly, there are few such miracle frames here. But Zone Eleven’s challenge is more immediate, to expand our understanding of Adams. Thankfully it’s up to the task. Until seeing this book I had not realized the extent of his professional gigs. Adams did not achieve true financial stability until later in his career. These photos capture him still in the hustle stage, working one gig after another through the 1950s and 1960s to make ends meet. Judging by these results he was quite competent as a pro. He did what needed to be done for the client. But for me, the photos do not go much deeper than that. I can sense no core visual signature which defines these photos as Adams’, no signal that he put much of himself into them. Erin O’Toole’s essay describes them as “midcentury Californian sensibility,” a phrase that damns with faint praise. Zone Eleven has the lukewarm aesthetic of an old corporate report or Time-Life annual. Informative, yes. Transcendent, no.

If its pages lack some punch, it may be baked into the book’s equation. The primary challenge of creating an Adams book is that his work is best viewed as silver gelatin prints. It’s in this form that one can pick out the elements that set his work apart: the tonal range, fine detail, and utopian promise of wilderness. On the printed page, with necessarily reduced size, resolution, and tonality, these powers are diminished. This holds true for most photographers, to some degree. But it’s especially relevant for Adams, who prided his output on the labors of previsualization, execution, and darkroom work. If the negative is the score and the print the performance, where does that leave the monograph? Somewhere in a grey area perhaps, around zone 5 or 6.

Zone Eleven contains many entertaining photos. I particularly love the pictures of mountaineers on Mt. Robson, the Cal football stadium, and the physics lecture hall at UC Irvine. Others will have their own favorites from these several dozen. Mandel’s deft sequencing highlights underlying pattens and in subtle and clever ways. But whether these scavenged frames cohere into any grand statement is less certain. This monograph feels a bit like a collection of B-sides and outtakes. Yes, we see it goes up to eleven, but that may not be enough to carry the day. It’s a provocative thought experiment for Mandel and for Adams scholars, and fans of Evidence will enjoy it too. But outside of those affinity groups, other readers may find it less essential.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

|

|

For Mandel, reconsideration is a routine habit. His landmark book Evidence (co-authored with Larry Sultan) set the standard for scrambled expectations in 1977. While Evidence sourced incredible photographs from reams of menial scientific and corporate literature, Zone Eleven reverses track, pulling banal moments from a celebrated oeuvre. Damiani describes Zone Eleven as a “a companion book to Evidence,” and it’s hard to argue. The monographs are comparably sized, with similar typeface, title placement, and cover design. The spines are eerily identical. It’s here that Mandel clarifies his collaborative intent, crediting the late Adams as co-creator. The dual-authored spine is the spitting image of Evidence, and the take-home lesson is the same in both books: context drives meaning. In Damiani’s words, “as Evidence reframes the institutional documentary photograph with new context and meaning, Zone Eleven responds to the audience expectation of ‘the iconic Ansel Adams nature photograph.’”

All well and good. But how are the pictures in Zone Eleven? If they’re not as strong as the ones in Evidence, that’s forgivable. Few photographs anywhere can stand up to the work in that book. Unsurprisingly, there are few such miracle frames here. But Zone Eleven’s challenge is more immediate, to expand our understanding of Adams. Thankfully it’s up to the task. Until seeing this book I had not realized the extent of his professional gigs. Adams did not achieve true financial stability until later in his career. These photos capture him still in the hustle stage, working one gig after another through the 1950s and 1960s to make ends meet. Judging by these results he was quite competent as a pro. He did what needed to be done for the client. But for me, the photos do not go much deeper than that. I can sense no core visual signature which defines these photos as Adams’, no signal that he put much of himself into them. Erin O’Toole’s essay describes them as “midcentury Californian sensibility,” a phrase that damns with faint praise. Zone Eleven has the lukewarm aesthetic of an old corporate report or Time-Life annual. Informative, yes. Transcendent, no.

If its pages lack some punch, it may be baked into the book’s equation. The primary challenge of creating an Adams book is that his work is best viewed as silver gelatin prints. It’s in this form that one can pick out the elements that set his work apart: the tonal range, fine detail, and utopian promise of wilderness. On the printed page, with necessarily reduced size, resolution, and tonality, these powers are diminished. This holds true for most photographers, to some degree. But it’s especially relevant for Adams, who prided his output on the labors of previsualization, execution, and darkroom work. If the negative is the score and the print the performance, where does that leave the monograph? Somewhere in a grey area perhaps, around zone 5 or 6.

Zone Eleven contains many entertaining photos. I particularly love the pictures of mountaineers on Mt. Robson, the Cal football stadium, and the physics lecture hall at UC Irvine. Others will have their own favorites from these several dozen. Mandel’s deft sequencing highlights underlying pattens and in subtle and clever ways. But whether these scavenged frames cohere into any grand statement is less certain. This monograph feels a bit like a collection of B-sides and outtakes. Yes, we see it goes up to eleven, but that may not be enough to carry the day. It’s a provocative thought experiment for Mandel and for Adams scholars, and fans of Evidence will enjoy it too. But outside of those affinity groups, other readers may find it less essential.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.