|

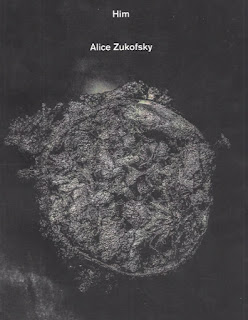

Him. By Alice Zukofsky

|

Photographs by Alice Zukofsky

Gato Negro Ediciones, Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. Unpaginated, black-and-white illustrations, 4¼x5¾x½".

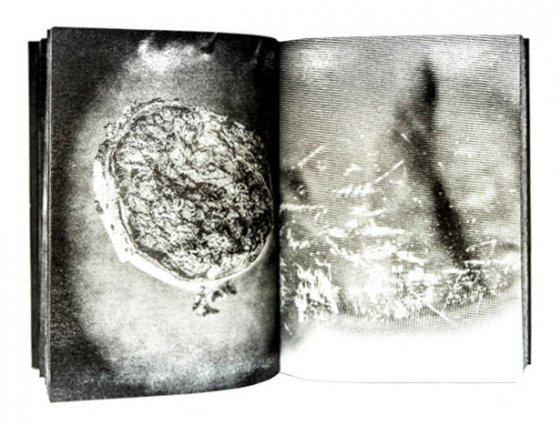

Alice Zukofsky’s Him, a Riso-printed book by Gato Negro Ediciones, speaks directly to the hands. Its chalky-smooth paper cover feels comfortable, worn in. The French-fold pages flip easily, like a deck of cards. Instead of the slow and stately procession of glossy pages that many contemporary hardcover photobooks demand, this book begs to be thumbed through, maybe even at speed. As the pages flip by, it creates an ambiance, a mysterious aura, not unlike the fantasy world of Chris Marker’s slideshow film La Jetée.

But the minute I sat down to write about it, I was struck with uncertainty. What are the pictures of? And, failing that, who is the photographer?

The book’s promotional materials bear an enigmatic blurb: “chronicle of a long night.” Indeed, the images are replete with darkness, the inky Risograph pages dense with shadow. One type of image recurs: a silver circle on a black ground. The circle seems to be filled with organic matter, reminiscent of Irving Penn’s cigarette butts. The publisher’s biography of Zukofsky — “Photographer and Mychologist [sic]” — tips the imagery in another direction. Do they depict the base of mushrooms, recently pulled from the earth? There’s more circular imagery — a stain, a pill broken on a sidewalk, the shield of a warrior in a marble frieze. The book concludes in a field of long grasses.

There aren’t many photographs that so fully resist words. In Alison Rossiter’s abstractions, writers lovingly catalogue the vintage materials that she sources on eBay. In Ellen Carey or Walead Beshty’s color abstractions, critics focus on the process of working with giant sheets of color paper in the dark.

|

Abstraction in photography isn’t exactly new. What, after all, is that jumble of shapes and shadows in the Nièpce plate, referred to as “the first photograph” and created around 1826? With a little help from the title, “View from the Window at Le Gras,” the mind sees the angles and says, “Roof.” Its vagueness is not the result of fading; scientists now understand that the picture was underexposed. There must have been other pictures that got too little light or too much, pictures that faded or shifted, pictures made accidentally, pictures that bloomed with chemical spills or reactions to light. But, when you put words to any of these, they become something. They lose everything when they’re no longer nothing.

So, the problem isn’t with photography. Photography can resist words. It’s writing that can’t. What do you say when you’re not sure what you see? Most critics focus on the artist. But, what happens when the artist is as elusive as her pictures?

This is what the publisher told me about Alice Zukofsky: “Interested in the microcosm and the planets beyond, Zukofsky’s travels have taken her on a journey across the world, having lived, studied, and worked, in places like Tanger [sic], Paris, Kolkata, La Habana, Buenos Aires, until she got to Mexico City in the mid nineties where she met her life-long friend and mentor, Leonora Carrington, and from where she hasn’t moved ever since.” On the surface, there is detail: a map of places, an artistic lineage. But, as soon as you pull the strands, they come loose, like soil crumbling.

|

Carrington, in her 1974 surrealist novel The Hearing Trumpet, described a room in which the furniture was painted, trompe l’oeil, on the walls. Like Zukofsky’s photographs, the images in Carrington’s novel are glancing dream-like pictures of the world, which dissolve when you try to hold them. It’s entirely appropriate that this book, which revels in the tactile, also resists identification with the three-dimensional world. There is a ground, but you can’t stand on it.

I was drawn to the depths and to the surface of this book simultaneously. It begs to be touched. It celebrates surface. The thick black pigment of the Risograph process promises depth, even as it denies access. In Mexico City where I first laid hands on it in the spring of 2022, most stores were still enforcing a sticky squirt of hand-sanitizer. The world has been a waking nightmare over the past two years. There are deadly, invisible, but natural forces that threaten our very being. The picture of this world shifts weekly. It is a mythic tale, telling and retelling itself like a crumbling landslide. Scientists are cast as mythic heroes. Their task is to debunk folk remedies straight out of a Carrington surrealist satire. As Luis Buñuel said of Carrington’s novel, “The Hearing Trumpet liberates us from the miserable reality of our days.”

Zukofsky’s book is likewise liberatory. It frees us from the realm of sense, of reference, of index: those stark lands of photographic non-fiction. Instead, this book is a new land where touch can be fantastical, dreamlike, otherworldly. Will we see more from Zukofsky? The publisher’s biography concludes inconclusively: “Rumours of her presumed death have been increasing since her last public appearance in 2011.”

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|