|

Photographs by Ralph Ellison

Steidl/Gordon Parks Foundation/Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust, 2023. 240 pp., 132 illustrations, 8¾x10½".

Take a bow if you knew that Ralph Ellison was a photographer. I admit I was blind to that fact until recently. I enjoyed Invisible Man as a youth, and I knew of Ellison’s importance in American literature. But Ralph Ellison as picture maker? I had no idea. It turns out he was an avid photographer, and not a bad one either. Along with countless shutterbugs in the post-war boom, he built his own home darkroom, lusted over equipment, and shot thousands of pictures spanning much of his adult life.

A handsome new monograph from Steidl explores this world for the first time. Its title Ralph Ellison: Photographer perates as a general description and also as artistic affirmation. It’s a joint effort, organized and edited by Ellison’s literary executor John F. Callahan alongside Michal Raz-Russo of the Gordon Parks Foundation. In Ellison’s photographic archives — safely housed with his papers at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC — the two were presented with a huge block of unformed clay. Virtually none of the images had been published or seen by the general public. Where to begin?

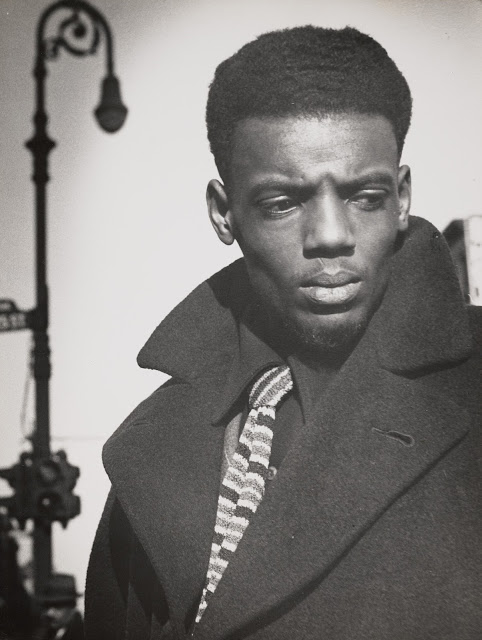

Their curation is enlightening if somewhat conventional. The book is loosely sequenced by date, and, within chronology, by subject. Photographs are drawn from two main bodies of work. First up are Ellison’s monochrome exposures from the late 1940s through the mid-1950s. This covers the period when Ellison first became enamored with photography, and his pictures are imbued with the excited rush of discovery. He’d settled in Harlem in 1936. After a brief WWII stint in the Merchant Marines, he returned to New York City for good. He befriended many artists, including Parks, and shot scads of film, which he later enlarged by hand as silver gelatin prints. The monograph paces eagerly through early photos of his wife and friends, city kids, and street candids. Occasionally Ellison was hired for paid gigs, but the bulk of his work was amateur, shot by and for himself.

|

The second and smaller chunk of Ralph Ellison: Photographer consists of color Polaroids from Ellison’s later years, shot long after he’d dismantled his darkroom. These come in a variety of formats beginning in the late 1960s, just after Ellison had endured a tragic house fire. Among his many lost possessions was the unfinished manuscript of his second novel. His subsequent photos reveal a charred soul in a ruminative mood, meditating over flowers, still lifes and household interiors. Perhaps these were fleeting grasps at pre-conflagration domesticity? Viewed now they document the same everyday items captured by a billion iPhones. In Ellison’s time Polaroids scratched the same possessive itch, and he shot over 1,200 of them, right up to his death in 1994.

Taken as a whole, both bodies of work — early b/w film and later Polaroids — form a collective portrait of an artist wrestling with photography over a long period. Pictures were no passing fancy for Ellison. They were an integral part his creative life, the visible counterpart to his anonymous titular protagonist. Adam Bradley’s introductory essay takes the hobby one step further, casting photography as a complement to his literary legacy. “A continuity of craft unites Ellison’s approach to both arts. At the center of his pursuit is discernment, a refinement of taste and intention that guides what he includes and excludes from his frame.”

|

Fine, but were his pictures any good? Well yes, but only to a degree. “No one would mistake these images for the work of a photographic master,” declares Bradley, and I think he’s right. They’re fine, but not earth-shattering. After an establishing pic of Ellison shot by Gordon Parks, the book’s opening passage features several portraits by Ellison of his wife Fanny. Some are quite strong with bold lines and tight compositions. They demonstrate a budding talent and an emotional resonance which is rare in young photographers. Fanny returns the favor with a few portraits of Ralph, also well-seen, as are Ellison’s portraits that follow. Langston Hughes makes an appearance, along with Albert Erskine and Mozelle Murray, all capably captured. It’s odd there are no pictures of Gordon Parks. He and Ellison were close, and it seems likely such photos exist. But perhaps they weren’t interesting enough, or the negatives were lost?

|

In any case, Ellison was a competent observer, even great on occasion. But he was right to keep his day job. His portraits are descriptive but they lack the je ne sais quoi which pushed contemporaries like Penn, Karsh and Ellison’s mentor Parks into rarified air. Ellison’s forays into street photography also demonstrate a sharp eye, but nothing to distinguish him from the great mass of Leica-toting mid-century humanists. There are grab shots of kids and crowds, muddy framing, city skylines and so on. As an insider’s take on mid-century African-American life, they are unique and important. But as pure photos, they are more pedestrian. This perspective is reinforced in the book with occasional contact sheets interspersed among the final photos. Perhaps they were intended as a deep dive bonus into the artist’s mind? Maybe so. But like most contact sheets they seem more routine than revelatory.

Oh well. If he wasn’t a world-class photographer, Ellison’s images are still informative. In fact, their amateur nature may be their most interesting facet. Ellison’s was a relatively unpolished view, grassroots, authentic and personal. Bradley again: “part of their appeal is the natural curiosity of an iconic artist working in a distant artistic field.” That curiosity is piqued about 2/3 through the book, when Ralph Ellison: Photographer finally hits its stride. A deft sequence of mixed monochromes begins with a snowy park scene. It’s followed by a brick wall abstraction, office equipment, interiors, a boat perfectly positioned upon a lake and (my favorite) a keenly layered jumble of car hood, poster and moving figure.

|

Viewing this bounty I realized that Ellison’s pictures had been sequenced by topic until this point. It was wonderful to see them roam unfettered, mingling easily with no documentary burdens. A final b/w photo of Fanny leads into the nice long suite of Polaroids which closes the book. The color snaps are quiet, unassuming and radiant. One can sense Ellison becoming more relaxed as a photographer, more accepting of the results, or maybe just worn down by life. By the book’s closing, the house fire has receded from memory. Youth’s creative flames have been extinguished, leaving behind just a faint trail of photographs, shot by a very visible man.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.