|

Night Calls. By Rebecca Norris Webb.

|

Photographs by Rebecca Norris Webb

Radius Books, Santa Fe, USA, 2020. 128 pp., 61 illustrations, 8½x9¾".

Drawing inspiration from W. Eugene Smith’s iconic photo essay Country Doctor (1948), Brooklyn-based photographer Rebecca Norris Webb spent six years regularly returning to Rush County, Indiana. This is the rural community where both she and her father were born, and where he subsequently worked as the community’s country doctor. Night Calls intimately chronicles her experience within this community, among its current residents, and her past recollections of Rush County.

Retracing her father’s professional routine, Norris Webb worked primarily at night and in the early morning hours, creating ethereal photographs of Rush County’s landscape. She juxtaposes these dreamlike scenes with tender portraits of her father’s former patients and, in some instances, their families, evoking the tight-knit, multigenerational nature of this community. Originally a poet, she deftly interweaves poignant texts rooted in her experiences and memories amidst her photographs. Night Calls is a multilayered portrait of this place and an extension of Norris Webb’s abiding interest in the relationships between people, memory, and the natural world.

Norris Webb took the time to speak with Allie Haeusslein about this most recent monograph, delving into greater detail about the underlying motivations and processes behind the making, editing, and completion of this deeply personal endeavor.

|

Allie Haeusslein (AH): In Night Calls, you lyrically address your perceptions and childhood memories of your father, his role in your rural county as a doctor, and your relationship to the landscape where you were raised. Do you remember the initial impetus for this project?

Rebecca Norris Webb (RNW): Night Calls is a project that I’d been thinking about since I was a young photographer at the ICP. That’s when I first came across Eugene Smith’s iconic Life photo-essay, Country Doctor. I remember thinking: How would a woman tell this story, especially if she happened to be the doctor’s daughter?

After finishing my second monograph, My Dakota, I finally had the creative space to begin this project. I work intuitively, so my first trips to Rush County were exploratory. I began to retrace the routes of some of my father’s house calls through this rural county where we both were born.

AH: In addition to relying on his handwritten patient logs, did you and your father talk about his recollections of working in Rush County?

RNW: My father was very much a collaborator, freely sharing his memories with me. Since he no longer travels, I was his eyes and ears in Rush County, bringing him back news of his former patients, which often sparked more memories.

Rebecca Norris Webb (RNW): Night Calls is a project that I’d been thinking about since I was a young photographer at the ICP. That’s when I first came across Eugene Smith’s iconic Life photo-essay, Country Doctor. I remember thinking: How would a woman tell this story, especially if she happened to be the doctor’s daughter?

After finishing my second monograph, My Dakota, I finally had the creative space to begin this project. I work intuitively, so my first trips to Rush County were exploratory. I began to retrace the routes of some of my father’s house calls through this rural county where we both were born.

AH: In addition to relying on his handwritten patient logs, did you and your father talk about his recollections of working in Rush County?

RNW: My father was very much a collaborator, freely sharing his memories with me. Since he no longer travels, I was his eyes and ears in Rush County, bringing him back news of his former patients, which often sparked more memories.

AH: Over the six years you worked on it, how did the form and content of Night Calls evolve?

RNW: During my third trip, everything shifted. That’s when I decided to echo his doctor’s work rhythms, photographing largely at night and in the early morning, when many of us come into the world — Dad delivered some thousand babies — and many of us leave it. All of a sudden, the project broke open for me, both emotionally and visually.

RNW: During my third trip, everything shifted. That’s when I decided to echo his doctor’s work rhythms, photographing largely at night and in the early morning, when many of us come into the world — Dad delivered some thousand babies — and many of us leave it. All of a sudden, the project broke open for me, both emotionally and visually.

|

AH: In addition to retracing his work rhythms, you talk about trying to evoke his “gentle bedside manner” when photographing his former patients and, in some cases, their families or descendants. What steps did you take to realize that demeanor in your process?

RNW: I’m rather shy, so I left many of the portraits until the last year of the project. That’s when I stumbled across my inspiration. I read how August Sander made portraits of German farmers “working much like a country doctor making house calls.” It dawned on me to try to channel Dad’s gentle bedside manner. As a doctor, he’s a man of few words, someone who listens closely and sees deeply. So, listening intently to his former patients’ stories — many involving a birth or near death — I worked with them to choose where in their home to make the collaborative portrait. More often than not, it was a doorway or window, which, like many of their experiences, were kinds of thresholds.

Since memories of my father were on their minds — and hinted at in their daydreamy gazes — I see these photographs, taken together, as a kind of slantwise portrait of Dad.

RNW: I’m rather shy, so I left many of the portraits until the last year of the project. That’s when I stumbled across my inspiration. I read how August Sander made portraits of German farmers “working much like a country doctor making house calls.” It dawned on me to try to channel Dad’s gentle bedside manner. As a doctor, he’s a man of few words, someone who listens closely and sees deeply. So, listening intently to his former patients’ stories — many involving a birth or near death — I worked with them to choose where in their home to make the collaborative portrait. More often than not, it was a doorway or window, which, like many of their experiences, were kinds of thresholds.

Since memories of my father were on their minds — and hinted at in their daydreamy gazes — I see these photographs, taken together, as a kind of slantwise portrait of Dad.

|

AH: “Slantwise” also describes the quality of the handwritten texts interspersed throughout Night Call. As with many of your other projects, text plays an important role here. Can you share more about the relationship between your writing and photographs in this body of work?

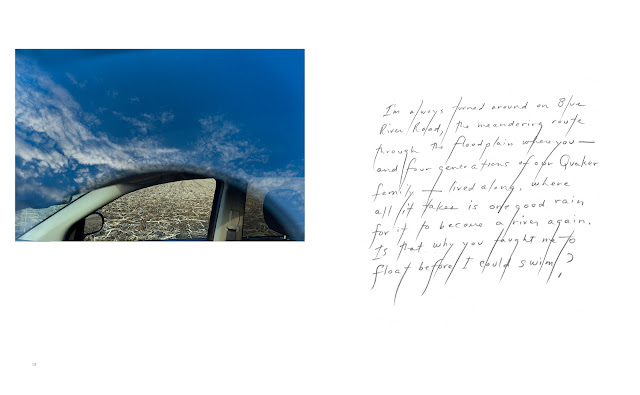

RNW: I think in images, whether I have a camera in my hand — or a pencil. That means that the photographs tend to come first, the words later on. Working in Rush County — where the landscape seemed to call to me — the beginning of the project was as much about listening as it was about looking. On foggy mornings while walking along Blue River Road — where Dad grew up and where our Quaker family lived for a hundred years — I found sometimes that the first lines of text pieces came to me. It was as if I could hear what I saw.

Only near the project’s end, did I settle on image and text pairings. Ideally, I hoped these photos/texts would expand our view of this landscape, sometimes by suggesting the more elusive metaphysical geography that lies outside the frame — including memory, history, reverie, as well as birth and death, suffering and compassion. “I have always aspired to a more spacious form,” to quote the poet Czeslaw Milosz. This has long been one of my photographic obsessions.

RNW: I think in images, whether I have a camera in my hand — or a pencil. That means that the photographs tend to come first, the words later on. Working in Rush County — where the landscape seemed to call to me — the beginning of the project was as much about listening as it was about looking. On foggy mornings while walking along Blue River Road — where Dad grew up and where our Quaker family lived for a hundred years — I found sometimes that the first lines of text pieces came to me. It was as if I could hear what I saw.

Only near the project’s end, did I settle on image and text pairings. Ideally, I hoped these photos/texts would expand our view of this landscape, sometimes by suggesting the more elusive metaphysical geography that lies outside the frame — including memory, history, reverie, as well as birth and death, suffering and compassion. “I have always aspired to a more spacious form,” to quote the poet Czeslaw Milosz. This has long been one of my photographic obsessions.

|

AH: What ideas most strongly guided your editing and sequencing process when you were conceiving the project in book form?

RNW: I try to edit intuitively, to let the rhythm and palette of a project guide me — slowly and organically — to the final sequence and shape of the book.

With Night Calls, the palette was varying shades of blues — from the ethereal blues of fog to the midnight blue of moonlit skies to the violet-blue clouds of thunderstorms, the color of a bruise. In Rush County, where the air is often heavy with humidity, you can feel the weight in your body. These Rush County blues — which sometimes feel part of you — are emotional hues as well. They are ever-shifting as water, the blues of transformation.

As I worked more deeply into the project, I began to see the shape of the book as meandering: passing through different kinds of weather, going back and forth in time — from the present to the near past to the distant past — while meditating on the relationship between memory and one’s first landscape, fathers and daughters, and the history that divides us as much as heals us. It seems fitting that the book’s sequence is as winding as Big Blue River, and perhaps as memory itself.

RNW: I try to edit intuitively, to let the rhythm and palette of a project guide me — slowly and organically — to the final sequence and shape of the book.

With Night Calls, the palette was varying shades of blues — from the ethereal blues of fog to the midnight blue of moonlit skies to the violet-blue clouds of thunderstorms, the color of a bruise. In Rush County, where the air is often heavy with humidity, you can feel the weight in your body. These Rush County blues — which sometimes feel part of you — are emotional hues as well. They are ever-shifting as water, the blues of transformation.

As I worked more deeply into the project, I began to see the shape of the book as meandering: passing through different kinds of weather, going back and forth in time — from the present to the near past to the distant past — while meditating on the relationship between memory and one’s first landscape, fathers and daughters, and the history that divides us as much as heals us. It seems fitting that the book’s sequence is as winding as Big Blue River, and perhaps as memory itself.

|

AH: Now that you have this beautiful book in hand, I have to ask: what does your father think of the finished monograph?

RNW: Not surprisingly, my father’s response when I’d asked him what he thought about Night Calls was another memory—one I’d never heard before. It was about a family who lived on a remote farm. Although one of the children had an alarmingly high fever, they were wary of this unfamiliar, young doctor on their doorstep. After helping bring down the toddler’s fever, however, Dad won the entire family over. They remained his patients for twenty years—and his personal friends, decades longer.

At the end of our phone call, his most heartening words, though, weren’t about Night Calls. He said that, thankfully, their family doctor saved her last two COVID-19 vaccines for Dad, who is now 100, and Mom, who is 93. Hearing the lightness in his voice, I smiled with relief. Their family doctor has definitely won me over.

Purchase Book

RNW: Not surprisingly, my father’s response when I’d asked him what he thought about Night Calls was another memory—one I’d never heard before. It was about a family who lived on a remote farm. Although one of the children had an alarmingly high fever, they were wary of this unfamiliar, young doctor on their doorstep. After helping bring down the toddler’s fever, however, Dad won the entire family over. They remained his patients for twenty years—and his personal friends, decades longer.

At the end of our phone call, his most heartening words, though, weren’t about Night Calls. He said that, thankfully, their family doctor saved her last two COVID-19 vaccines for Dad, who is now 100, and Mom, who is 93. Hearing the lightness in his voice, I smiled with relief. Their family doctor has definitely won me over.

Purchase Book