“Dairy farmers wanted female calves from their annually pregnant heifers. These calves, The Glorious Girls, were tendered with care and, as soon as they were stable on their hooves, photographed by men; men only. Dad documented every female calf born on his farm using his Polaroid camera. The calf, always front and center, always looking her best.... Bull calves were a disappointment. Unwanted and unworthy of photography...In contrast, farmers wanted their regularly pregnant wives to give them sons, to work on the farm and inherit its land and herds. Daughters, pretty distractions, were inconvenient.”

“Mum cooked, I helped. Conforming behavior. Mum didn’t so much as teach me as she did ‘perform woman.’ I was expected to take notice, note The Obligations, follow her lead. Which wasn’t her lead at all. Mum was being led, down the proverbial garden path, around the show-ring, led by an invisible rope that I didn’t know existed until years after leaving the farm. She was tied, tied to the farm as wife.”

— Odette England, Dairy Character

|

In his brilliant novel The Hamlet, William Faulkner describes a scene in which Ike Snopes, the “idiot,” tries to have sex with a cow. Ike, described as a “man-child,” had already imagined a romantic relationship with the cow throughout the book before he tried to consummate his love in a scene that Faulkner depicts as equally tragic, hilarious, compassionate, poetic, and gorgeous. As it develops, Ike’s libidinous intentions are thwarted when the cow shits all over him. In the astute, modernist imagination of Faulkner the scene takes on mythic proportions, and he uses it as a way to decode power structures and gender roles in the American South. In Faulkner’s mind all of us are some form of Ike or the heifer, our expectations for life always thwarted by imposed expectations, roles and our sexuality.

In Dairy Character, by Odette England published with Saint Lucy’s Books, the artist probes similar metaphors as she reflects on her own childhood spent on a dairy farm in Australia. The book offers an experimental approach to photography while providing text for a personal story about social power, repression, rebellion, and self-actualization.

There are essentially three different types of photographs England utilizes for developing her narrative: Her own pictures, made with an exceptional black-and-white palette, are a mixture of close-up photographs an androgynous looking child’s skin and those she made on trips back to the family farm. She also includes archival photos and snapshots made during her childhood, both family pictures and Polaroids made by her father to document the farm. Most surprisingly, she inserts crudely processed photographs from an old manual published to help dairy farmers — enlargements of udders and other body parts. Similarly, the book itself is divided into three distinct sections, in a sort of A-B-A structure, with a section of photographs, followed by a written narrative in which England provides a recounting of her childhood through fragments of letters from her mother juxtaposed with her own reminiscence about life on the farm, and finally another selection of photographs.

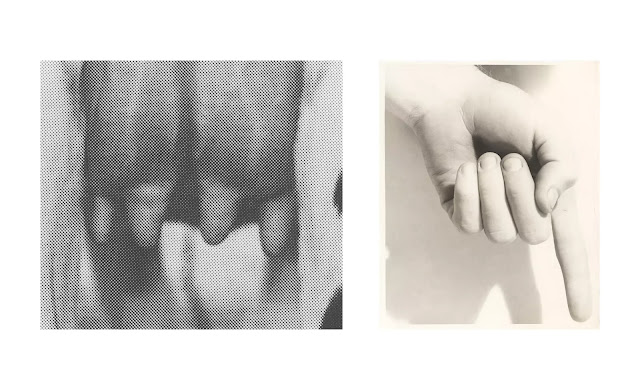

In her first book, Keeper of the Hearth: Picturing Roland Barth’s Unseen Photograph, England demonstrated tremendous strength through her sensitivity in juxtaposing images. Typically combined to highlight formal or compositional similarities, she evokes complex questions and ideas by placing pictures side-by-side, coaxing new meaning from the images. A clinched hand with a finger pointing has tremendous visual similarities with a cow’s udder, the exposed wires of a ceiling light similar to a girl’s hair cascading down her back, or a shadow across a child’s chest like a bird’s wings in flight. Each of these juxtapositions help articulate an essential part of England’s narrative about conflicts involving gender identity, cultural expectations and self-determination.

|

Throughout her text, England talks about the role photography played within her family and life on the farm, hinting as to why she found a voice with the medium. For her father, the camera was a way to document The Girls, the heifers he prized as his legacy and livelihood. For her mum, it was a way to document family life, and also why she is always absent from the pictures, an important metaphor in England’s narrative: “She is the working photographer, the front-of-the-of-house, the cook — never the chef — the waitress, the dishwasher. Her presence is there in other ways, other ways made visible to her camera. Without these ways, mum is lost to memory. Lost to labor. Lost to wife.” Recognizing these patterns and the power of photography, England found a new space in between these predetermined roles, taking control of the camera to define her own presence (in resistance to her mother’s absence), and to define her own gender identity (in response to the patriarch’s expectations).

England uses text very much like she does photographs, juxtaposing fragments to piece together larger ideas. The bulk of the text section is composed by short recollections of England looking back on her childhood. These recollections are short, and typically focus on patterns and expectations presented to her as a child — clearly delineating the expectations of men and women on the family farm — while also emphasizing roles each of them played in her family drama. Her father oversaw The Girls and the family’s economic livelihood, while her mother kept the home and raised the children.

|

|

Within these memories, England articulates a conflict she felt about all this early in life, constantly labeling her own behavior as “conforming” or “nonconforming.” Interspersed among these childhood recollections are letters, presumedly sent to England by her mother but always signed “Mum & Dad.” The inclusion of these letters cements the basic ideas at the heart of the narrative, reminding her of the duties, hierarchies, and expectations that shaped her early life, all defined by her sexual body.

The design of the book is simple and effective. The cover images beautifully anticipate the narrative to come, with the front showing a detail of human skin, folded and creased like a contorted body, while the back shows a disembodied hand squeezing a cow’s hide, together pointing out awkward, utilitarian, and commodified bodies. The book uses two different colors of paper to add the flow of the narrative, the two large sections of photographs printed on a bright white stock and the text on a pale pink. This use of color seems obvious in creating a narrative about gender, but also refers to a childhood memory in which England wanted to paint her bedroom a lovely shade of pink. I must confess to finding this use of paper the least successful part of the book, Odette’s narrative is much too good to use such a simply conceived metaphor.

In recent years, Odette England has revealed herself as an extremely versatile, ambitious, and interesting artist, a force to be reckoned with in contemporary photography. Her three recent books — Keeper of the Hearth: Picturing Roland Barth’s Unseen Photograph, Dairy Character, and Past Paper//Present Marks: Responding to Rauschenberg — all demonstrate different approaches to photography, and all have tremendous visual acúmen. Dairy Character is the most overtly autobiographical of these works (though all art is autobiographical). It relates the story of a woman of enormous character and strength, who has overcome backwards expectations on a path to self-realization, while also reminding us of the tremendous power of photography as a tool for creating and subverting expectations.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

Brian Arnold is a photographer, writer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY. He has taught and exhibited his work around the world and published books with Oxford University Press, Cornell University, and Afterhours Books. Brian is a two-time MacDowell Fellow and in 2014 received a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Institute for Indonesian Studies.