"Studying the work of Darrel Ellis is like witnessing the eruption of an inner life, multiple lives captured through one work of art."

— Tiana Reid

In 1987, the United States houses of Congress passed the Helms AIDS Amendments. These amendments were created to prohibit the use of any federal funds to provide HIV/AIDS education, information, or prevention materials, and any information or activities that could be perceived as condoning homosexual activities. I grew up in the 1980s and lost a family member to the AIDS epidemic. I remember many conservative leaders calling AIDS “gay cancer,” and bumper stickers that read things like Thank God for AIDS and Kill a Queer for Christ. There is no denying that HIV/AIDS was a divisive issue during the 1980s — like Roe v. Wade or gun control today — with a clear majority of conservative leaders not only feeling the government had no obligation to educate or protect the population from the infection, but even actively promoting the belief that the virus was God’s way of punishing gays for their sinful choices.

During the 1980s, I also grew up in a city surrounded by an extremely violent African American gang war, between the Crips and the Bloods, and I saw firsthand black neighborhoods forgotten by the city and run as open drug markets. Drive-by shootings and assassinations were commonplace. My public high school was in the middle of this violence. The police were a daily presence. At one point, I even witnessed a gang related shooting on the front steps of the school. As a white man I won’t pretend that I can understand what it means to grow up Black in America, but I can say that I had a clear window into the violence and pain eroding their communities at that time.

|

Looking back at these experiences, it seems that to be black, gay and HIV positive was to embody some of the key cultural conflicts of the day, representing essential moral questions about community, compassion, identity, and mortality. Living with all these labels, I imagine, could only lead to deep personal conflict, fueling anger and acute feelings of isolation. Artist Darrel Ellis was all these things, a gay black man born in New York in 1958 who died of AIDS complications 34 years later, on 4 April 1992. Before Ellis was born, his father was beaten to death by two police officers (in the 1980s there would be no question of accountability). His father was also an avid photographer, and eventually all his negatives and equipment were given to Darrel. These photographs became the foundation of his studio practice, providing the resources for a remarkable meditation on family and identity, now documented in the great new book published by Visual AIDS, Darrel Ellis. The book is richly illustrated with photographs, drawings, and paintings by the artist, as well as a curated collection of critical and biographical essays, interviews, and roundtable discussions that collectively help contextualize and humanize his unique contributions as an artist.

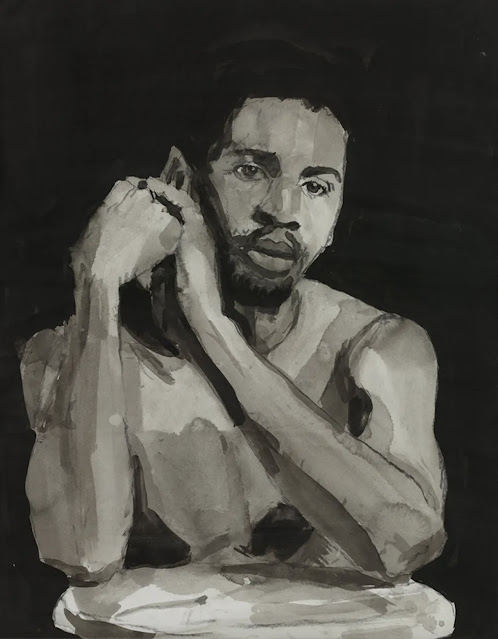

I must confess I knew nothing about Ellis before opening this book, although I did recognize his face. Both Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe made photographs of Ellis, portrayed clearly by both with compassion and as a kindred spirit, as an artist and member of the gay community in New York City (the roundtable discussion printed in the book does question this, however, and suggests that these photographs were driven by a white gaze). As a gay black in the 1980s, Ellis’s life seemed destined for tragedy — similar in some ways to both Hujar and Mapplethorpe — and yet, somehow, he left behind an incredibly sensitive, humble, beautiful, and curious body of work, one that fuses traditional techniques in drawing and painting with experimental approaches to photography and darkroom practice. I find it interesting that his drawings and paintings demonstrate a great photographic sensitivity — the majority of this work is created in monotone, and clearly derived from photographs (Ellis has a famous self-portrait based on Mapplethorpe’s portrait) — while his photographs are based on a unique and experimental approach to the darkroom, offering confusing and interesting images based on material experimentation. The book also contains numerous quotes from Ellis’s journals, with passages like this pointing to his philosophies of materiality and experimentation: “Material must be used [.] We are matter, but we must use it to convey reality [,] that which is beyond our present physical consciousness [,] our limitations.”

|

|

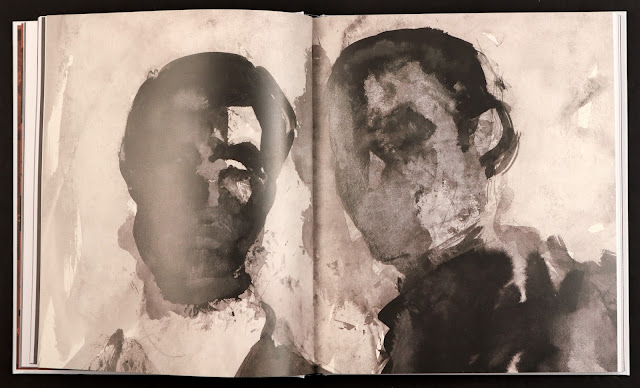

There are two primary threads at play in Ellis’s work, self-portraits and pictures based on family snapshots. Within these is also the repeating motif of identities under erasure: faces that appear distorted, obscured, hidden, or even obliterated. Whether the result of gestural abstractions found his drawings and paintings, or the darkroom distortions utilized in his photographs, faces in Ellis’s work are usually indiscernible, removed or opaque. Referencing family snapshots, these images reflect incredible ideas about family and memory, and also offer a remarkable metaphor for Black life in the United States during the 1980s. Curiously enough, Ellis’s self-portraits offer an exception, and are really the only works in his oeuvre in which a face or an identity appear clearly composed and tangible. Looking at these works together, his self-portraits juxtaposed with the obscured faces of his family and friends, reveals a tremendous personal and cultural conflict, identities forgotten and abandoned, and yet also a self grasping for individual definition and self-determination. Another cited passage from Ellis’s journal, in which he ruminates on his process of obscuring figures and memories, offers a lovely summary: “I feel strongly that deconstructing is all right. But what’s more important is reconstructing. It’s very cerebral work, very mental work, and, in a way, very soulful work.”

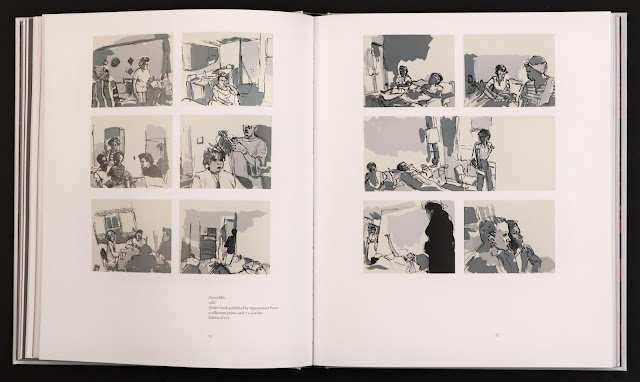

Ellis’s photographs are curious and take a bit of time to understand. These pictures are all reworkings of his father’s negatives. To make his new work with these negatives, Ellis projected them onto three dimensional forms — layers of blocks, circles, or non-geometric plaster configurations — which are then rephotographed. Ellis would position his camera at an angle, so his finished images are often elongated, receding across the printed page, creating yet another layer of distortion (the book provides a great explanation for how he made this work, complete with illustrations detailing his process). Ellis would take these negatives to a lab for development and to have a new, inter-negative produced (photographing the projected negative would result in a positive image) and then use these to make his own prints. The resulting images are obscured and confusing, with blocks and geometric shapes dividing the image into new layers and unrecognizable faces and events, with the position of his camera creating bizarre angles that make the image appear to be receding into space or melting onto the photographic paper.

|

In Ellis’s own words, “The forms I use to project upon are all different, and the negative, when it interacts with the form that I’m projecting upon, causes certain kinds of distortion. Some of the forms I use are round, some are rectangular, some are biomorphic. That one straight photographic image representing people and a picnic — I project that image on this geometrical shaped form and you get a totally different image than if I project it on something that’s more biomorphic. They’re all different, the photos; they’re like regeneration, regenerated. From one you get many. And that works as a metaphor for family.”

Artist Allen Frame, a close friend who took responsibility for Ellis’s estate after his death in 1992, offers a slightly different perspective on this work, “He used geometric forms — circles, squares, and horizontal bars — to obliterate central parts of the image, creating mysterious symbols that suggest both discord and harmony,” and he goes on to say, “The overlaying geometric forms act as an aggressive intervention, yet help resolve and complete compositions that, unlike his father’s, are vaguely defined.”

|

|

Quietly, Ellis emerged as an accomplished artist with an interesting educational background and important acknowledgements from his peers. During most of his productive years, he worked as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art (even using his ID badge as source material for his photographic work), which Ellis cites as an essential part of his own artistic education and philosophies; he considered himself unique among Black artists of his day, fully entrenched and a part of the European traditions that filled the galleries at MoMA. He also worked in a residency program at PS1 and participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program in 1981. In 1989, his work was included in the seminal exhibition organized by Nan Goldin in response to the AIDS crisis, Witness: Against Our Vanishing. Shortly after his death, Peter Galassi included his photographic work in New Photography 8, alongside artists Dieter Applet (an extremely interesting pairing with Ellis), Ellen Brooks, Dennis Farber, Robert Flynt, Mary Miss, Gunduala Schulze, and Toshio Shibata. His work was also included in Deborah Willis’s important history of black photographers, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers.

|

If you are unfamiliar with Visual AIDS, the publisher of Darrel Ellis, it is worth learning more about them. Found in 1988, Visual AIDS is a contemporary arts organization committed to raising AIDS awareness and creating dialogue around HIV issues today. They produce unique and interesting exhibitions, public forums, and publications. They are committed to representing visual artists living and working with HIV/AIDS today, and to preserving, archiving, and honoring the work of artists active during the height of the epidemic. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement and another viral crisis, Darrel Ellis is an extremely timely and important publication, and provides an interesting look at artist who died before his vision was fully realized, but nevertheless left behind unique and challenging visual investigations about race, identity, and morality. The book provides a great introduction to the work done by Visual AIDS and has left me curious to see more from the organization.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Brian Arnold is a photographer, writer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY. He has taught and exhibited his work around the world and published books with Oxford University Press, Cornell University, and Afterhours Books. Brian is a two-time MacDowell Fellow and in 2014 received a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Institute for Indonesian Studies.