|

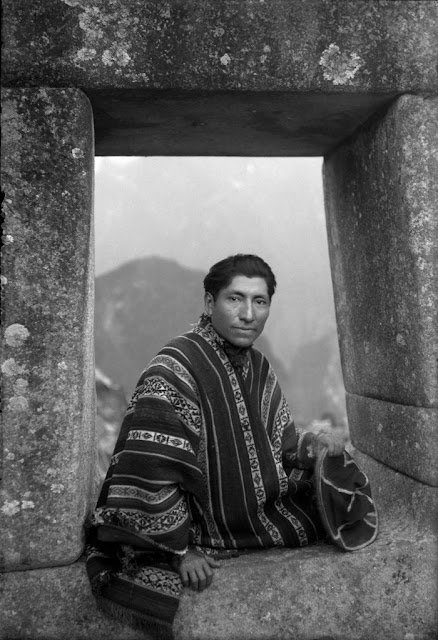

Photographs by Martín Chambi

Editorial RM, 2022. 194 pp., 170 illustrations, 9½x11¼x¾".

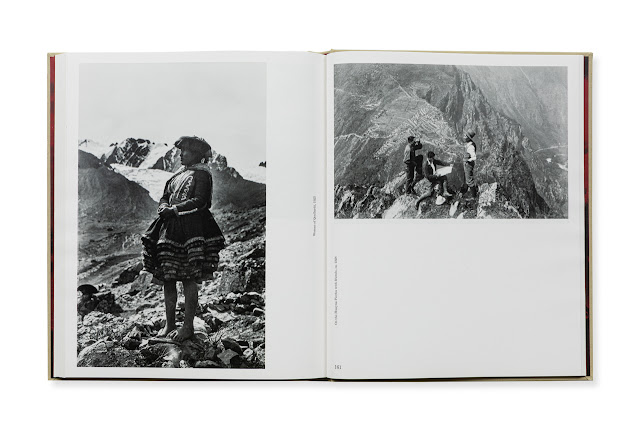

This publication of the photographs by Martín Chambi in the Jan Mulder collection, Lima, is a welcome addition to books dedicated to this Cuzco photographer, who lived from 1891 until 1973. This nicely printed collection of over one hundred photographs is organized in three sections: The first thirty photographs are devoted to Inca archaeological sites, with some twenty focused on Machu Picchu. A second group, also of thirty pictures, is predominately focused on well-selected views of Cuzco. The third sequence is then dedicated to mostly portrait work, with fifteen of these pictures being self-portraits.

Particular attention has been given in the book’s production. Numerous vintage prints are reproduced with the warm tonalities associated with materials used in the early twentieth-century, when most of Chambi’s images were made. This strategy is particularly successful in rendering his large plate views of Machu Picchu and Cuzco. It is to Mr. Mulder’s credit that he has chosen to emphasize these well-chosen vintage works, and to the publisher, Editorial RM, for committing the resources to give readers the pleasure of seeing these early prints in convincingly appropriate tonalities.

Chambi is quoted as being especially concerned with making the legacy of the Inca remains known to the general public through his photographs. This book goes a long way to emphasize his personal, even spiritual, identification with the legacy of Inca culture. But an equally strong case should be made for his commitment to documenting the Quechua culture of which he was a part. He began serious documentation of indigenous life in the early 1920s, supported in part by his role as graphic correspondent for Lima publications la Crónica and Variedades. Over the next thirty years, he continued to photograph native Quechua people, their villages and festivals throughout the Cuzco region. These pictures comprise a unique and irreplaceable archive of Peru’s Quechua culture, and much work still remains to be done in organizing and publishing them. Unfortunately, only a handful of ethnographic views appear in this book, causing a very important aspect of Chambi’s work and personal life to be only passingly referenced.

|

One unusual aspect of Chambi’s archive featured in this book, however, is a selection of self-portraits that he made throughout his life. It has been known for some time that he took great interest and pride in recording not only his expeditions, exhibitions, studio work and gatherings, but also in portraying his own personality and personal activities. In the book’s final essay, Horacio Fernandez examines Chambi’s self-portraiture within the context of an engaging and well-informed discussion of his life and work. He explains how many of Chambi’s self-portraits were precisely staged and executed, how some required a collaborator, and how some emphasized important aspects of his personality. Fernandez writes, “As we have seen, he synthesized his life story as a pilgrimage in search of Quechua culture in contemporary life, colonial fusions, and Inca ruins. In addition to these themes, there were also the characters, the roles — traveler, explorer, Indian — he played for the camera in other self-portraits.”

|

Juxtaposed against some telling examples of Chambi’s commercial studio work and some ethnographic pictures, these self-portraits give us a vibrant sense of Chambi himself and his relationship with the world in which he lived and worked. Fernandez also addresses important issues, such as our contemporary impulse to define an artist’s agenda based on only a few selected images. He has picked up on the need to distinguish Chambi’s work from that of his contemporaries, particularly of his colleague Juan Manuel Figueroa Aznar, with whom he worked at Machu Picchu in 1928. Almost all of their pictures published in the 1934 book Cuzco Histórico, for instance, were reproduced without author attribution, resulting in a confusing scenario for understanding each photographer’s work. He also does not shy away from discussing the cultural complexities associated with the now well-known pictures of Cuzco Indigenous subjects by the celebrated New York portraitist and fashion photographer Irving Penn, who worked briefly in a rented Cuzco studio in 1948.

|

Other texts in this book provide additional, informative back matter, but nearly every text page is marred by a design strategy where a number of the words ending a paragraph are not aligned with the left text margin. The appearance of these words, centered and floating below blocks of text, is both confusing and unattractive. Mulder’s introductory text outlines his growing fascination as a collector with preserving and understanding Chambi’s work and Peru’s photographic legacy. Andres Garay’s assessment of Chambi as “A Photographer Made to the Measure of Cuzco” gives us an authoritative summary of the beginnings of Chambi’s career in Arequipa and his successful early work upon settling in Cuzco. As one of Peru’s leading photo-historians, Garay’s commitment to investigating Chambi’s work and early 20th-century Peruvian photography exemplifies the kind of serious research into the country’s photographic history that has been sorely needed. The contribution by the Ecuadorian writer Francois Laso, “The Silent Progress of Martín Chambi’s Photography”, does not match the qualities of the two other essays, but does provide an appreciative eye regarding different aspects of Chambi’s work as seen from a neighboring Andean country.

|

The pictures, of course, are the enduring reason for this publication, and the layout and tonal quality of the prints will hold attention over many viewings. In particular, the four-page fold-out of Chambi’s stunning panorama of Machu Picchu, made circa 1940 with two joined 18 x 24 cm glass plates, is especially impressive, and even though cropped slightly at the top of the image, is a remarkable, unprecedented achievement in the publication of Chambi’s work.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

©Krista Elrick

|