|

By Luce Lebart and Marie Robert.

|

Text by Luce Lebart and Marie Robert

Thames & Hudson, London, United Kingdom, 2022. 504 pp.

I feel compelled to begin this with a selection from the iconic poster produced by the Guerrilla Girls in 1988 (see link for full text):

The Advantages of Being a Women Artist:

Working without the pressure of success

Not having to be in shows with men

Having an escape from the art world in your 4 free-lance jobs

Knowing your career might pick up after you’re eighty

Having the opportunity to choose between career and motherhood

Being included in revised versions of art history

Not having to undergo the embarrassment of being called a genius

Thirty-five years later… I pick up this weighty compendium, A World History of Women Photographers, with a sigh of contextual disappointment: is it possible that we are still having this conversation? That I am about to dive into what must, in fact, be considered a revised version of art history?

|

I am a cis-gendered female artist, raised to fiercely believe that I could do anything and be anything, gender notwithstanding. I internalized a message that the battlegrounds of gender equality were behind us, that only slight hiccups might remain on what was clearly a linear path to parity. (Ahem. A pause here, another sigh: “Between 2000 and 2017, work by women artists accounted for less than 4% of total art sold at auction.”)

My initial studies of photography were in France, home to a history of the medium pointedly used by editors Luce Lebart and Marie Robert as a site of a significant (or, particularly egregious) male dominance of the narrative of photo history. In Paris, in my early twenties, I was woefully — blissfully — ignorant of the sexism at play in the field there. Yes, we trooped around the city to galleries that mostly displayed the work of male artists; I was having too much fun to notice. Yes, it was made clear that a career in photojournalism was best suited for a certain masculine swagger; again, I barely noticed — a shrug of disinterest from a 24-year-old me, already more invested in other manifestations of the medium. (Another pause: the gender gap in photojournalism is quite real.)

|

|

I do not excuse my obliviousness. I suppose when one wants to believe that the historically stacked deck has been, or is being, corrected, one might blithely ignore reality. (One more quick interruption of a related reality, via the Census bureau: women in the United States earned 30% less than men in 2020.) A revelation: the stacked deck isn’t even subtle! Can you hear the loud POP of a toxic bubble bursting around my naïveté?

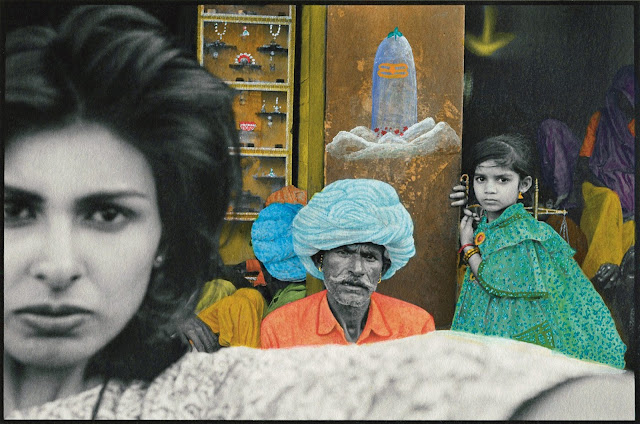

A World History of Women Photographers is an exquisite effort to tell an expanded story of photography’s history, and one I wish I knew earlier. A huge tome of 504 pages, with 450 photographs, it focuses on showcasing the work of individual photographers rather than the myriad lurking reasons why we might not already know them. In an introductory text, Marie Roberts briefly chronicles and contextualizes why some of these histories have been diminished (passively) or shoved aside (actively); we read of domesticity’s quotidian demands, gendered marketing strategies and of direct denigration of female artistic production.

|

The authors err on the side of kindness and gentleness toward the pernicious depths of historical misogyny at play. They note: “With this collection of artists, it is not so much a matter of producing a counter-narrative or of deconstructing histories that already exist but of completing them. We have no desire to burn idols or topple statues, only to erect new ones, and to create a narrative that is richer and more fair.” In this spirit, I tiptoe back from an ugly-statistics-statue-toppling kind of mood, and I allow myself to bask, with enormous pleasure, in the works of the 300 women showcased herein.

The vast majority of the names in this book are new to me, although there are plenty of names that do already have legitimate footholds in the canon (from A to Z and almost spanning the chronology with Anna Atkins and Zanele Muholi). One hundred and sixty international women writers contributed texts to accompany each sumptuously printed image, and we are regaled with biographical snippets and anecdotes amid historical context for each photographer. Organized chronologically by birthdate, the book is a glorious, methodical march through time and space (almost 200 years, across every continent).

|

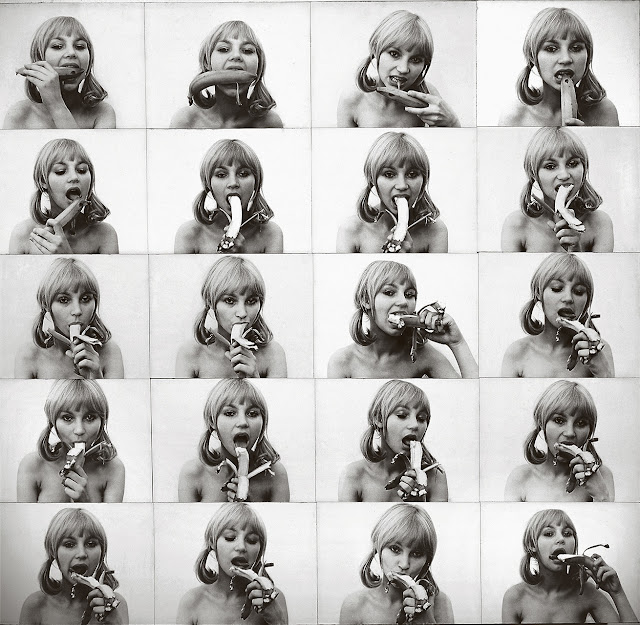

I return again and again to flip through this book, allowing myself to be infuriated as I read of underrecognized artist after underrecognized artist. There are too many delightful discoveries to enumerate, so I will only tease with a few. I relish the experimental modernism of Katalin Nádor in Hungary and Gertrudes Altschul in Brazil. I am struck by the social documentary work of Rosa Szücs in Spain and Marie el-Khazen in Lebanon, and by the significant — and mostly unknown to me — role of women in documenting political turmoil throughout the twentieth-century. Most importantly, I find myself awash in a spectacularly undefinable, sprawling vision of photography’s potential. Simply: here we see some of the many, many talented women who have picked up cameras, played in the darkroom, used and shaped a malleable medium. And we should know this work.

Amid it all, I stumble across an actual toppled statue (of Lenin, headless, from Masha Ivashintsova in 1985).

|

|

This is a reference book that I will hold near and dear. For years, I have participated in an extraordinary endeavor, #First Day First Image, which hopes to begin to right/re-write a historically skewed canon by being attentive to how educators shape students’ very first encounters with photographic imagery. We must ask, ad nauseam, who is represented, and whose story is being told. Let’s build some new statues.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|