|

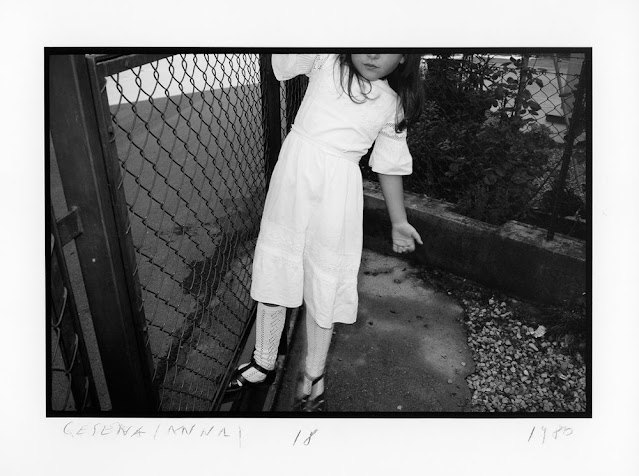

Di sguincio, 1969–81. By Guido Guidi.

|

Photographs by Guido Guidi

MACK, London, UK, 2023. 144 pp., 11¾x9½".

Photographers are a restless lot. Just when you think you’ve got one pinned down, they’ll take an unexpected detour. Guido Guidi is a case in point. After a long career of innovation, teaching, and widespread influence, The Italian master had seemingly settled into a nice groove at 82. Ten years ago he’d collaborated with Mack to publish Preganziol, 1983, a gorgeous remembrance of shifting tonalities set inside one small room. That monograph was a breakout hit, and other titles soon followed. Guidi and Mack collaborated on seven more over the next nine years.

Although each monograph had its own theme and quirks, Guidi’s monographs often followed a similar blueprint. Every tome offered a deep dive into a single project from his vast archive. Some were mammoth, filling multiple volumes. Most were tidier. His pictures generally hewed close to home, exploring the region near Cesena, Italy with a large format camera and color film. His work was distinguished by an innate sense for color, the charming quirks of serial exposure, and the singular light of northern Italy. These components helped Guidi to stake out an aesthetic territory that was distinctly his, and recognizable at a glance.

|

Guidi’s latest monograph, his ninth with Mack, Di sguincio, 1969-1981 breaks with most past conventions (Lunario and Dietro Casa hinted in its direction, but we’ll set those aside for now). Not to say this book is forward-looking. Not to say this book is forward-looking. On the contrary, it hopscotches back in time, bypassing Guidi’s color era to drop in on his monochrome thirties. The title dates the photos from 1969 through 1981, but the vast majority are from a narrow time window, 1977 - 1980. As evidenced by these in-your-face transgressions, this was a period of serendipitous informalism for Guidi. It would eventually culminate in his transition to large-format color, when he turned the page on youthful happenstance. But that would come later. In the 1970s, he was knee-deep in the period’s snapshot zeitgeist. He used a hand-held camera loaded with b/w 35 mm film, supplemented with accessory flash. He fired away from close range, early and often. The photos recall Mark Cohen’s Grim Street and Barbara Crane’s Private Views (both shot roughly contemporaneously, then published later). Guidi’s are spicier and more intimate.

|

|

If the book comes across as somewhat half-cocked, that’s a fair description of his early methods. These are not refined visions, nor are they meant to be. Influenced by the early work of Sternfeld, Cohen and Nathan Lyons, Guidi favored spontaneity over thought. He often shot from the hip without looking through the viewfinder. Keep the pesky left brain at bay, or at least that was the non-thinking. The result? “They’re rather childish photographs. I took them joyfully, playfully,” he tells Antonella Frongia in the book’s interview. He compares “instant” photography with the automatic writing of the Surrealists and the instinctive approach of Jim Dine. “Photography has allowed me to access my unconscious in a very immediate way,” he says, in what might serve as a motto for this book.

|

Coming out of left field, and without much warning, Di sguincio lands as something of a minor masterpiece. Guidi’s touch is light and fleeting. His photos are stuffed with unexpected forms and streaks, a pleasure to browse. As usual, Mack’s reproductions set a high standard. Guidi took great pride in his original prints, and they’ve been faithfully duplicated with pencil marks, smudges and stamps. But the aspect which makes Di sguincio most enjoyably jarring is that it’s such a change of pace. Through book after book to this point, Guidi had carefully constructed an Italy of open spaces, ponderous contemplation and wise old brick walls. Di sguincio tears it all down without a second thought. These old pictures are claustrophobic, busy, flippant, irrepressible. If the formal color work is classical music, these have the energy of punk rock. You thought monochrome film snapshots were dead? It turns out they still live and breathe.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.