|

Hunting In Time. By Ronit Porat.

|

Photographs by Ronit Porat

Sternthal Books, 2023. In English. 192 pp., 6¾x9½".

Raindrops on roses, whiskers on kittens… I asked my students this week to list their favorite photographed things, emphasis on photographed. (And, of course, the inverse: things that automatically raise eyebrows or make them cranky when in photographic form.) It is useful to know what makes us let down, or put up, our guard, what makes us instantly melt or bristle. My own bright-copper-kettle pleasure points are as follows: clocks, owls, negatives, shadowy enigma, pointed anonymity, archival deep dives, dead birds, tools in deadpan still life, reworked narratives where truth is slippery, and fictions enticing. This partial list was generated while in the thrall of Ronit Porat’s Hunting in Time — as if this book wrote this list for me, reminding me of each and then sequentially checking the boxes.

This is the tale of a murder. Almost a century ago, several teenagers attempted to rob a clockmaker in Weimar Berlin, and he wound up dead. No pun intended. A cacophony of midnight-clanging clocks interrupted the robbery, the perpetrators were spooked, the clockmaker was killed. He had a side gig, dabbling in producing pornographic photographic material in the back room, often starring… you guessed it, one of the future murder suspects. Lengthy — and internationally publicized — murder trials ensued, invoking sexual deviance and underage consent, as well as the ethical foundations of a society in flux.

|

I said this was a tale, but it is not exactly a narrative. This book is based in multiple exhibitions that the author put together based in and around the archival record of this murder. An essay by Ines Weizman provides a larger societal framework for the murder and its aftermath, helping to contextualize much of the photographic material that Porat was able to mine, as well as her methodological approach. Gender politics are invoked, as is encroaching Nazism, biological clocks, trauma, and the tale of a box of stereoscopic photographs that were supposed to be burned but were not.

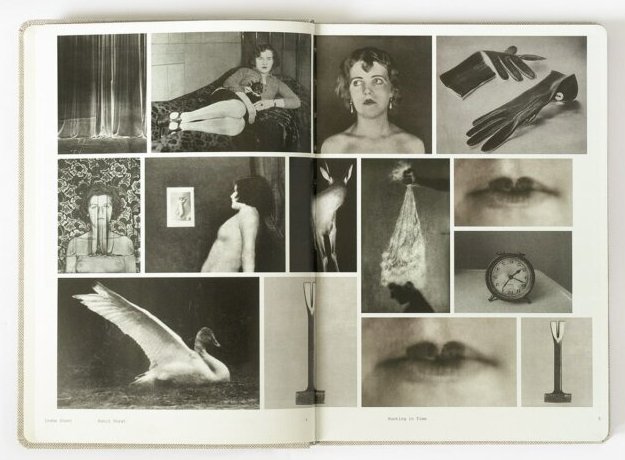

Composed of an astonishing breadth of photographic source material, the images weave a complicated and haunting web of associative thought and non-linear pathways. The murdered clockmaker’s photographic record of an obsession with young women serves as a starting point, as do images sourced from contemporaneous publications supporting a then-burgeoning interest in studies of criminal psychology. Fashion magazines, supply catalogues and patent application sketches (handcuffs, corsets) all add to Porat’s repository of suggestive enigma. There are stern owl eyes, limp dangling rabbits, birds in flight and birds on hands, female bodies in motion and female bodies at rest, watchmaking and surgical implements, gloved hands, and cigarettes.

|

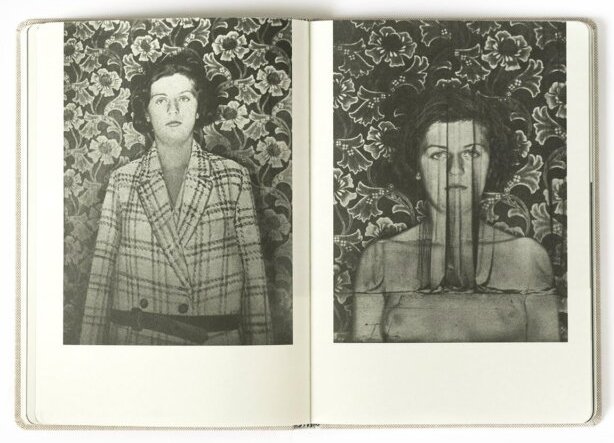

Meticulous documentation of the photographic source material lies enticingly at the back of the book. I spent a not-insignificant amount of time indulging in scratching the itch of the raison d’être of each photograph. Sources range from Ilse Bing to eBay and from Walker Evans to Etsy; photographer unknown was responsible for many. The artist absorbed and physically translated each gleaned photograph with equal-opportunity care; a photograph of a chastity belt in a Parisian museum was lifted from howstuffworks.com and rendered as a negative, followed two pages later by the swan half of Francesca Woodman’s interpretation of Leda and the Swan, similarly inverted and astonishingly arresting. Each image is absorbed into the visual logic of the whole. Singular photographs coexist with multiple exposures and spliced montages; the intermingling of whole and fragment, comfort and danger, predator and prey is allowed to mirror the murky confusion of the tale itself. A rich gamut of monochrome possibilities is represented, simultaneously luminous and shadowy, with tonal ranges in shades of gray, permutations of sepia, and purple-browns.

|

There is no true-crime-podcast resolution here, neither redemption nor indictment for any of the protagonists. Within this humble, linen-bound cover, I read an invitation to speculate on the power of the archive, and a simultaneous reminder of its inherent futility. Or, our own photographic gaze and its consequences (as maker or audience) is as unreliable, and influenced by cultural milieu, as that of the many photographs produced in and around the murder of a clockmaker-pornographer in Berlin, a century ago. And these photographic musings are a few of my favorite things.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|