|

Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal.

|

Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists

Writings by Rebecca Bengal

Interview by Brian Arnold

Aperture, New York, 2023. 216 pp..

In his second collection of essays, Why People Photograph?, Robert Adams addresses the difficulty in finding good writing about photography. Too many writers, he says, get bogged down in critical jargon and unnecessarily complex rhetoric, a sort of writing he defines as “social-scientific balloon bread.” I’m inclined to agree that there isn’t much great writing about photography, but when a good writer comes around it’s easy for me to get excited about reading their work.

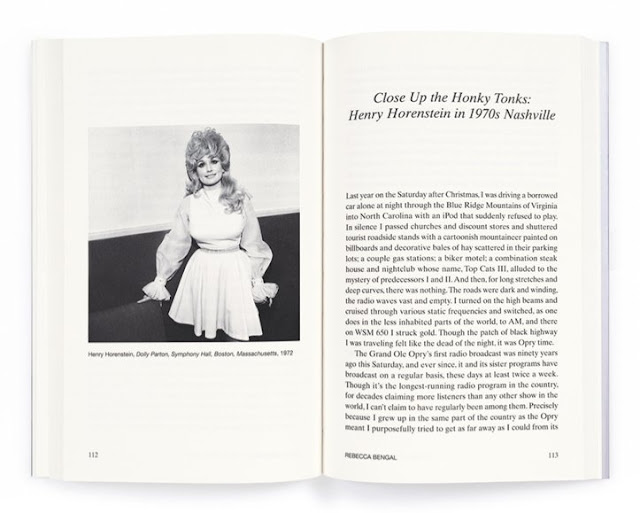

I’ve been familiar with Rebecca Bengal’s writing from her contributions to many great photobooks published in recent years — Dark Waters, Girl Pictures, and Juggling is Easy, to name a few — and thus found myself eager to dig into her new collection of essays published by Aperture, Strange Hours. There is a lot I could say about this book, but to keep it simple, it is clear, concise, and insightful writing about an incredibly interesting and diverse collection of photographers, lacking any of the jargon or unnecessary rhetoric Adams dismisses. Some of my favorites are the essays about Judith Joy Ross and Ming Smith, the short story written for Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures, and an interview with Henry Horenstein about his Nashville work. It quickly became clear to me that interviews are a major part of Bengal’s practice as a writer. There are two reproduced in the book — the one with Horenstein and another with Nan Goldin — but in many of the essays Bengal references interviews she conducted with the artists either in person or by phone. With that in mind, I wasn’t far into Strange Hours before I had the idea that the right way to respond to the book would be with an interview with her. Bengal originally reached out to me after my review of Dark Waters and I used that as entry point for a new connection. What started as a simple and unrelated email exchange resulted in this interview, developed between November and December 2023.

When/how did you first get interested in photography? Do you make pictures or just write about them?

Hard to say, but well before I was aware of it, I think. Turns out quite a few of the photographers I’d eventually come to admire actually were making pictures in and around where I grew up, pre-internet rural western North Carolina, a place that as a kid I assumed was invisible to the rest of the world. Now, looking back, Mary Ellen Mark’s pictures of girls smoking in a kiddie pool, Duane Michals’ portrait of my hometown witch, Joel Sternfeld’s Nags Head photographs, are all cryptically fused with my own memories. I wrote about this unconscious, belated influence in “Self Portrait in Other People’s Pictures” (a piece which is not in Strange Hours).

I do make pictures too, but my conscious interest in photography came sideways, and later. In undergrad in Greensboro, North Carolina, I was primarily involved with the creative writing program, writing and reading fiction, and film, and art — and also music, because music was what my friends’ social lives centered around. I would find my way to different photographers through magazines — art and music and fashion magazines, skate magazines — and old books and through photographer friends. The first major photographer I remember meeting was Sally Mann, when she came to give a lecture at our school. I think she was working on what would become her book What Remains, and she was hauling around this giant bucket of decomposing liquid and photographing it in different stages of decay.

I took my first darkroom class around that time; we worked out of the same darkroom the police department still used then (this was the late 90s). I was experimenting, learning, having fun. Photography sometimes showed up in my short fiction, but I didn’t really write about it for years.

|

| Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal |

You grew up with a deaf parent? Does that have anything to do with your interest in photography?

My father has been profoundly Deaf from birth, as is his brother, as was their father, as was many of his siblings and his father — Deafness and different forms of sign language have been part of my father’s family for six or so generations. My mother is hearing, we all sign. My sister Joanna Welborn, who is also hearing, is a photographer — her work is incredible. Maybe for my sister and I, in our separate ways, gravitating to photography has to do with being aware of the visual in a different, heightened way. My father is definitely inclined that way — I love the films he used to make and the pictures he makes now.

But photography, for me, is about language too. Beyond growing up bilingual in English and sign, I also absorbed different accents, writing, music, and in that way photography is another language too. In “Slowly and with Much Expression,” an essay in Strange Hours about the relationship between words and images, I write about growing up with closed captioning in a time when it wasn’t common for anyone to use it unless you were Deaf.

DoubleTake magazine is mentioned several times in Strange Hours. Can you tell us a bit about your time with DoubleTake? How did you come to work at the magazine? What was the nature of your work? How has the vision of Double Take influenced your work and career?

The mainstay of my many revolving odd jobs in undergrad was at a small independent bookstore and newsstand in a shopping center in Greensboro, North Carolina. We had a giant wall of magazines and while the gambling tip sheets and car manuals were most popular with our clientele, tucked in among those I found this beautiful literary and photography quarterly magazine DoubleTake. When I found out it was published at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, less than an hour away, I wrote them a letter and asked if they were looking for interns. The internship paid a little more than minimum wage, but it did pay, and I primarily worked for the fiction editor, reading manuscripts and suggesting edits. I just really soaked up whatever I could, helping the nonfiction editor too, sitting in with the photo editors, proofing books, helping out with other programs at the Center.

Things were changing rapidly at DoubleTake then and I became an editorial assistant. And just a few more months and the magazine was effectively shuttered. A skeleton staff moved up to Cambridge, where one of the founders, Robert Coles, was based, but none of our jobs were guaranteed, and I had no desire then to move to Boston, where I knew no one. I think they continued for a year or two like that before it was shuttered again. Others have tried to revive it and duplicate it since then and it never works out. DoubleTake was strange and radical and earnest and exciting and also very expensive to make, and it was the work of an immensely talented group of people, several of whom I’ve worked with and/or remained connected to since and its influence has long outlasted its several years of existence.

But photography, for me, is about language too. Beyond growing up bilingual in English and sign, I also absorbed different accents, writing, music, and in that way photography is another language too. In “Slowly and with Much Expression,” an essay in Strange Hours about the relationship between words and images, I write about growing up with closed captioning in a time when it wasn’t common for anyone to use it unless you were Deaf.

DoubleTake magazine is mentioned several times in Strange Hours. Can you tell us a bit about your time with DoubleTake? How did you come to work at the magazine? What was the nature of your work? How has the vision of Double Take influenced your work and career?

The mainstay of my many revolving odd jobs in undergrad was at a small independent bookstore and newsstand in a shopping center in Greensboro, North Carolina. We had a giant wall of magazines and while the gambling tip sheets and car manuals were most popular with our clientele, tucked in among those I found this beautiful literary and photography quarterly magazine DoubleTake. When I found out it was published at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, less than an hour away, I wrote them a letter and asked if they were looking for interns. The internship paid a little more than minimum wage, but it did pay, and I primarily worked for the fiction editor, reading manuscripts and suggesting edits. I just really soaked up whatever I could, helping the nonfiction editor too, sitting in with the photo editors, proofing books, helping out with other programs at the Center.

|

| Nan Goldin, C.Z. and Max on the Beach, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976 |

Things were changing rapidly at DoubleTake then and I became an editorial assistant. And just a few more months and the magazine was effectively shuttered. A skeleton staff moved up to Cambridge, where one of the founders, Robert Coles, was based, but none of our jobs were guaranteed, and I had no desire then to move to Boston, where I knew no one. I think they continued for a year or two like that before it was shuttered again. Others have tried to revive it and duplicate it since then and it never works out. DoubleTake was strange and radical and earnest and exciting and also very expensive to make, and it was the work of an immensely talented group of people, several of whom I’ve worked with and/or remained connected to since and its influence has long outlasted its several years of existence.

For me, so young then, working at DoubleTake and CDS was an introduction to a lot of artists and writers — William Gedney, for instance — both within and outside of documentary work. It was an introduction to the community work and films and books that CDS was involved in. It was an introduction to the ethical questions around documentary. And for me, it was liberating in the sense that the magazine treated photography and writing as equals, not something that was required to literally illustrate the other.

In recent years, you’ve contributed writing to some really interesting photobooks by Danny Lyon, Kristine Potter, Justine Kurland, and Peggy Nolan, among others. How are these writings composed? Are they developed collaboratively with the photographers? Or based solely on looking at the pictures? Do you have relationships with these artists that help develop your writing?

They are all so different, everyone. Kristine Potter knew some of my connections to music and to the places of her pictures in Dark Waters, which has an undercurrent of murder ballads in the American South, especially Tennessee, where she lives, and North Carolina. We talked — but we didn’t even discover exactly how much we have in common until well after the book was published. I tried to sort of absorb the pictures the way I knew the songs, and then I went away and wrote a story, I didn’t want to pin it too specifically to any of the pictures: They are absolutely stunning on their own. The story I wrote (at the invitation of Kristine and editor Lesley A. Martin, who both were open to let me do whatever I wanted) came from two characters I already had in mind, and from my memory of the pictures or, even more accurately, the feeling I had looking at them. I’m really proud to have been a part of this book.

That’s similar to the way I went about writing another short story, “The Jeremys,” for Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures. I first met Justine years ago when she came to Austin, Texas, and parked her van in my best friends’ backyard while she was still making some of her narrative photographs of feral, runaway girls, pictures in which I saw my past, present, future, and fictional selves in. Justine has made so many brilliant bodies of work since, and I’ve written about many of them, but she and editor Denise Wolff gave me the freedom to write a story that is from the point of view of imagined girls in the pictures.

I love that lots of people read Carolyn Drake’s Knit Club and thought I was right there in Water Valley, Mississippi, when Carolyn Drake was making the pictures. I wasn’t — I was brought in much later, but that book was particularly collaborative in terms of many conversations with Carolyn and Paul Schiek at TBW. Because of the way the photographs work, none of us thought it should be too directly representational, but something a bit more nebulous, and so I ended up interviewing several of the women in the pictures and piecing together a semi-fictional story in their words. Carolyn sought my feedback on the sequencing and design she was working on with Paul, and it was fascinating to see it evolve. A beautiful and perfect design.

Speaking of Paul and TBW, who are one of my favorite photobook publishers around, I didn’t know Peggy Nolan at all prior to working on Juggling Is Easy, but Paul had a feeling I’d love her photographs of her teenage kids and their friends in 1980s Florida, and he was sure right. Peggy is a live wire, tremendously talented and such a force, and in her case I wanted to tell her story as much as the stories of the photographs.

I first wrote about Danny Lyon’s The Bikeriders several years ago but we didn’t meet until 2020, when I happened to be in the Southwest, and we did this interview. Last year he invited me to write an essay for a catalogue for his solo exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum of Art. I wrote about his films, which I love. Danny surprised me by including a photograph he made of me on the day of our interview in the exhibition: it was the day after Election Day 2020, and I’m all masked up.

Can you say something about how Strange Hours was put together? Is it a “greatest hits” selection of your writings? Or was there a more directed selection process?

The initial invitation to publish Strange Hours came courtesy of one of my wonderful editors at Aperture. Brendan Embser saw the possibility of a book in the stories and essays I’d been doing for their books, the magazine, the blog, and PhotoBook Review over the past several years.

Brendan and assistant editor Varun Nayar and I looked at a ton of my writing to decide what to include. Much of the book would come from my work with Aperture, and many of those pieces have a strong narrative element (Diana Markosian, Judith Joy Ross, Chauncey Hare, for instance), and of course the short story I wrote for Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures. So that established a core. From there we each made a list of pieces we hoped to include. The book is part of the Aperture Ideas book series, which all adhere to a set length, so that left us with a certain amount of space to work with. Also, since the Ideas series is text-focused, it’s designed for just one image per piece, plus a well of color photographs. For me, that eliminated a few pieces that I felt would be better served by multiple pictures — for instance, the semifictional story I wrote for Knit Club. But I had to eliminate many other favorites, and favorite artists.

We also didn’t want to worry too much about an overall theme. While story is the heart of the book, even if it’s just the story of an encounter with an artist and their pictures, I also wanted to include some different kinds of writing, essays, short fiction, interviews, and to create plenty of ways for anyone to enter in — whether or not they know anything about photography. “In the Place Where Prince Lived” might not seem to be about photography, for example, but it is about my and Alec Soth’s attempt to find something of Prince through the act of photographing the people who live in the places where he once did. It’s layered in with Alec also being a photographer who shares a hometown with Prince — and, for a few years, practically shared a backyard. And it’s layered in with our discovery along the way that Prince himself was retracing his own steps photographically in the months before his death.

Almost all of the pieces had been published before, but I knew I wanted to heavily revise many of them. I was able to add back in a significant and previously unpublished portion of an Eggleston interview I did years ago, in which he talks about photographing inside Graceland. This is where the book’s title (which my editor suggested) comes from: At one point, Eggleston reckons that, like Elvis, he keeps “strange hours.” And when we were choosing the cover, it wound up being a lesser-known photograph by Eggleston, too, and that gave us the purple of the cover (thanks also to the excellent designers at Pacifica). But I revised almost every piece to some extent, working with Brendan and editor Susan Ciccotti. I’ve also published pieces since our print deadline that I wish could be in Strange Hours, but we were able to include just one entirely new piece that I wrote specifically for the book: I wanted to add something that spoke more to ambiguity and perceived truth, and to a literary sense of photography, and that ended up being Yevgenia Belorusets’ stories and photographs from Ukraine. And then, I want to mention, I am deeply grateful to the flat-out brilliant Joy Williams, my teacher and friend, one of our greatest writers, who wrote the foreword essay.

Is there a photographer you’ve never connected with or written about but would like to?

Oh, there are so many photographers whose work I love but haven’t had the chance to write with/about at the right time — far too many to mention. Lately, mostly I’m interested in writing with or in response to, rather than about. To either collaborate in the way I’ve done on some photobooks, whether it’s for a book or some other form, in all the ways I just described to you. And/or to collaborate in the sense of working on a story together. Where you’re doing some true fieldwork collectively, as I’ve gotten to do with Joel Sternfeld on the youth climate movement, and at Standing Rock first with Alessandra Sanguinetti, with Justine Kurland after the fires near Paradise, for example. Or and especially something a little bit looser, like the stories I’ve done with Alec Soth.

Mostly, I think about all the writers and artists and filmmakers and musicians I wish I could have met or studied with. I’ll limit myself to just two photographers here who are no longer with us. First, Corita Kent, who had a wholly uncanny, playful, and experimental way of teaching and seeing the world; Ordinary Things Will Be Signs For Us, a collection of her work, was recently published by J&L Books. The other is Larry Sultan. While working on this piece about him with Alec, and especially after I wrote it, talking with Larry Sultan’s colleagues and close friends, particularly Jim Goldberg, and Larry’s wife, Kelly, I was magnetized, all over again, by Larry’s ideas and intellect and, very important, his sensibility and sense of humor. Mack is doing lovely reissues of his books; the most recent is Swimmers. As Kelly Sultan, a wonderful writer herself, once wrote: “Asking big questions by examining the mysteries of daily life was how Larry tended to approach picture making; he was always hoping to capture something just off stage, a ‘strange creature’ that would be revealed only after the picture was printed.”

One of my favorite essays in Strange Hours is the one about Prince, the project you did with Alec Soth. With that in mind, what’s your favorite Prince song or record?

Prince left the world too soon, but he left us here with so much. No way to nail down a favorite, though I love having my socks knocked off by hearing a song I haven’t heard in a while (like “Black Sweat,” one of his later ones, at a dance party recently). And when Alec and I were visiting Prince’s houses in and around Minneapolis, and leaving the story itself up to discovery, Paisley Park was just beginning to dig into the famous vaults he left behind. Some of the reissues and compilations of rare and previously unreleased work that have come out since are truly excellent — check out the albums Originals, Welcome 2 America, and Piano and a Microphone 1983.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

Brian Arnold is a photographer, writer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY. He has taught and exhibited his work around the world and published books, including A History of Photography in Indonesia, with Oxford University Press, Cornell University, Amsterdam University, and Afterhours Books. Brian is a two-time MacDowell Fellow and in 2014 received a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Institute for Indonesian Studies.

In recent years, you’ve contributed writing to some really interesting photobooks by Danny Lyon, Kristine Potter, Justine Kurland, and Peggy Nolan, among others. How are these writings composed? Are they developed collaboratively with the photographers? Or based solely on looking at the pictures? Do you have relationships with these artists that help develop your writing?

They are all so different, everyone. Kristine Potter knew some of my connections to music and to the places of her pictures in Dark Waters, which has an undercurrent of murder ballads in the American South, especially Tennessee, where she lives, and North Carolina. We talked — but we didn’t even discover exactly how much we have in common until well after the book was published. I tried to sort of absorb the pictures the way I knew the songs, and then I went away and wrote a story, I didn’t want to pin it too specifically to any of the pictures: They are absolutely stunning on their own. The story I wrote (at the invitation of Kristine and editor Lesley A. Martin, who both were open to let me do whatever I wanted) came from two characters I already had in mind, and from my memory of the pictures or, even more accurately, the feeling I had looking at them. I’m really proud to have been a part of this book.

|

| Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal |

That’s similar to the way I went about writing another short story, “The Jeremys,” for Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures. I first met Justine years ago when she came to Austin, Texas, and parked her van in my best friends’ backyard while she was still making some of her narrative photographs of feral, runaway girls, pictures in which I saw my past, present, future, and fictional selves in. Justine has made so many brilliant bodies of work since, and I’ve written about many of them, but she and editor Denise Wolff gave me the freedom to write a story that is from the point of view of imagined girls in the pictures.

I love that lots of people read Carolyn Drake’s Knit Club and thought I was right there in Water Valley, Mississippi, when Carolyn Drake was making the pictures. I wasn’t — I was brought in much later, but that book was particularly collaborative in terms of many conversations with Carolyn and Paul Schiek at TBW. Because of the way the photographs work, none of us thought it should be too directly representational, but something a bit more nebulous, and so I ended up interviewing several of the women in the pictures and piecing together a semi-fictional story in their words. Carolyn sought my feedback on the sequencing and design she was working on with Paul, and it was fascinating to see it evolve. A beautiful and perfect design.

Speaking of Paul and TBW, who are one of my favorite photobook publishers around, I didn’t know Peggy Nolan at all prior to working on Juggling Is Easy, but Paul had a feeling I’d love her photographs of her teenage kids and their friends in 1980s Florida, and he was sure right. Peggy is a live wire, tremendously talented and such a force, and in her case I wanted to tell her story as much as the stories of the photographs.

I first wrote about Danny Lyon’s The Bikeriders several years ago but we didn’t meet until 2020, when I happened to be in the Southwest, and we did this interview. Last year he invited me to write an essay for a catalogue for his solo exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum of Art. I wrote about his films, which I love. Danny surprised me by including a photograph he made of me on the day of our interview in the exhibition: it was the day after Election Day 2020, and I’m all masked up.

|

| Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal |

Can you say something about how Strange Hours was put together? Is it a “greatest hits” selection of your writings? Or was there a more directed selection process?

The initial invitation to publish Strange Hours came courtesy of one of my wonderful editors at Aperture. Brendan Embser saw the possibility of a book in the stories and essays I’d been doing for their books, the magazine, the blog, and PhotoBook Review over the past several years.

Brendan and assistant editor Varun Nayar and I looked at a ton of my writing to decide what to include. Much of the book would come from my work with Aperture, and many of those pieces have a strong narrative element (Diana Markosian, Judith Joy Ross, Chauncey Hare, for instance), and of course the short story I wrote for Justine Kurland’s Girl Pictures. So that established a core. From there we each made a list of pieces we hoped to include. The book is part of the Aperture Ideas book series, which all adhere to a set length, so that left us with a certain amount of space to work with. Also, since the Ideas series is text-focused, it’s designed for just one image per piece, plus a well of color photographs. For me, that eliminated a few pieces that I felt would be better served by multiple pictures — for instance, the semifictional story I wrote for Knit Club. But I had to eliminate many other favorites, and favorite artists.

We also didn’t want to worry too much about an overall theme. While story is the heart of the book, even if it’s just the story of an encounter with an artist and their pictures, I also wanted to include some different kinds of writing, essays, short fiction, interviews, and to create plenty of ways for anyone to enter in — whether or not they know anything about photography. “In the Place Where Prince Lived” might not seem to be about photography, for example, but it is about my and Alec Soth’s attempt to find something of Prince through the act of photographing the people who live in the places where he once did. It’s layered in with Alec also being a photographer who shares a hometown with Prince — and, for a few years, practically shared a backyard. And it’s layered in with our discovery along the way that Prince himself was retracing his own steps photographically in the months before his death.

Almost all of the pieces had been published before, but I knew I wanted to heavily revise many of them. I was able to add back in a significant and previously unpublished portion of an Eggleston interview I did years ago, in which he talks about photographing inside Graceland. This is where the book’s title (which my editor suggested) comes from: At one point, Eggleston reckons that, like Elvis, he keeps “strange hours.” And when we were choosing the cover, it wound up being a lesser-known photograph by Eggleston, too, and that gave us the purple of the cover (thanks also to the excellent designers at Pacifica). But I revised almost every piece to some extent, working with Brendan and editor Susan Ciccotti. I’ve also published pieces since our print deadline that I wish could be in Strange Hours, but we were able to include just one entirely new piece that I wrote specifically for the book: I wanted to add something that spoke more to ambiguity and perceived truth, and to a literary sense of photography, and that ended up being Yevgenia Belorusets’ stories and photographs from Ukraine. And then, I want to mention, I am deeply grateful to the flat-out brilliant Joy Williams, my teacher and friend, one of our greatest writers, who wrote the foreword essay.

|

| William Eggleston, Untitled, ca. 1983-86 |

Is there a photographer you’ve never connected with or written about but would like to?

Oh, there are so many photographers whose work I love but haven’t had the chance to write with/about at the right time — far too many to mention. Lately, mostly I’m interested in writing with or in response to, rather than about. To either collaborate in the way I’ve done on some photobooks, whether it’s for a book or some other form, in all the ways I just described to you. And/or to collaborate in the sense of working on a story together. Where you’re doing some true fieldwork collectively, as I’ve gotten to do with Joel Sternfeld on the youth climate movement, and at Standing Rock first with Alessandra Sanguinetti, with Justine Kurland after the fires near Paradise, for example. Or and especially something a little bit looser, like the stories I’ve done with Alec Soth.

Mostly, I think about all the writers and artists and filmmakers and musicians I wish I could have met or studied with. I’ll limit myself to just two photographers here who are no longer with us. First, Corita Kent, who had a wholly uncanny, playful, and experimental way of teaching and seeing the world; Ordinary Things Will Be Signs For Us, a collection of her work, was recently published by J&L Books. The other is Larry Sultan. While working on this piece about him with Alec, and especially after I wrote it, talking with Larry Sultan’s colleagues and close friends, particularly Jim Goldberg, and Larry’s wife, Kelly, I was magnetized, all over again, by Larry’s ideas and intellect and, very important, his sensibility and sense of humor. Mack is doing lovely reissues of his books; the most recent is Swimmers. As Kelly Sultan, a wonderful writer herself, once wrote: “Asking big questions by examining the mysteries of daily life was how Larry tended to approach picture making; he was always hoping to capture something just off stage, a ‘strange creature’ that would be revealed only after the picture was printed.”

One of my favorite essays in Strange Hours is the one about Prince, the project you did with Alec Soth. With that in mind, what’s your favorite Prince song or record?

Prince left the world too soon, but he left us here with so much. No way to nail down a favorite, though I love having my socks knocked off by hearing a song I haven’t heard in a while (like “Black Sweat,” one of his later ones, at a dance party recently). And when Alec and I were visiting Prince’s houses in and around Minneapolis, and leaving the story itself up to discovery, Paisley Park was just beginning to dig into the famous vaults he left behind. Some of the reissues and compilations of rare and previously unreleased work that have come out since are truly excellent — check out the albums Originals, Welcome 2 America, and Piano and a Microphone 1983.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

| Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal |

|

| Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal |

Rebecca Bengal is the author of Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists (Aperture, 2023). Her writing about art, literature, film, music, and the environment has been published by the Paris Review, Vogue, Vanity Fair, the New York Times, Oxford American, Southwest Review, the Believer, the Guardian, and the Criterion Collection, among many others. She has contributed short fiction and essays to books by Kristine Potter, Carolyn Drake, Justine Kurland, Paul Graham, Danny Lyon, Peggy Levison Nolan, and Charles Portis. A MacDowell fellow in literature and a former editor at American Short Fiction, DoubleTake, and Vogue, she holds an MFA from the Michener Center for Writers in Austin. Originally from western North Carolina, Bengal lives in Brooklyn.