|

How to Raise a Hand. By Angelo Vignali

|

Photographs by Angelo Vignali

Witty Books, Italy, 2022. 128 pp., 7¾x9¾".

Photographic series about hands were added to my list of (playfully) banned subjects a number of years ago, where they would join cats and fire hydrants as too cliché-prone, and thus best avoided. A reliable trope of interest among undergraduate students is the flesh of hands, usually tender youthfulness countered by images showing what other flesh has endured over various spans of manual labor or sun.

Clearly, my presumption of inevitable cliché was a mistake. Angelo Vignali’s How to Raise a Hand is a book of fingers and hands, and I could not love it more.

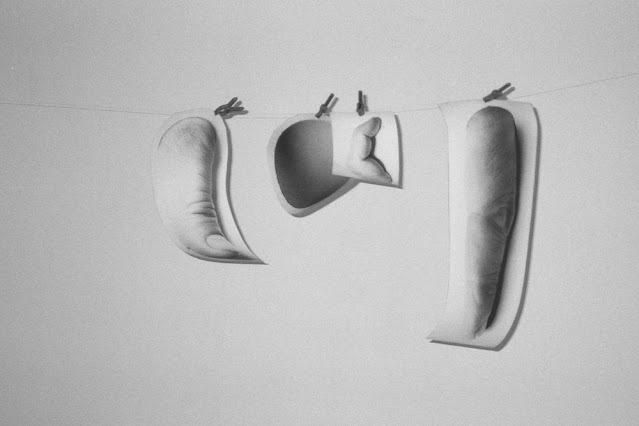

The book is divided into six chapters that are bookended by a prologue and an epilogue. Each chapter is photographed within the space of the artist’s sparse studio, and each is a tight edit on a singular motif. In one, we observe photographs of sculptures representing fingers, in another, improbably large photographs of fingers spill out of a box. We see these photographs pinned to a clothesline, absurd giant fingers dangling in space. We see suit jackets unpacked from bags to be hung neatly on a coatrack, and then joining the fingers, floating on almost invisible line. The jackets lose the mold of the human body they once shielded, as the fingers did through the act of being rendered two-dimensional, flat — armatures of flesh rendered futile.

|

|

Chapter IV arrests me, disarms me. No pun intended. The individually printed images of disembodied fingers are montaged together, on page after page, into a pointed cacophony of digits. No pun intended, again. Each is cut out with no apparent underlying logic; some follow the contours of hooked fingers, others are typologically rectangular. The only hints of color in the book lie within this chapter: a few brief moments of yellowing paper hint at black-and-white processing stains, two magenta fingers jolt, tease me. Once the alarm of finger isolation (dissection?) passes, I realize that each finger is displayed by poking upward through a cardboard hole, pushed up and isolated against a sterile background. Some shyly lurk at the hole’s edge, others flop, flaccid, onto their examining table.

Each chapter reads as a delicate study of a specific object, or set of objects, in this quiet studio. Subtle shifts of the camera’s vantage point underline the sense of a sustained study; a redundancy holds us, grounds us, in each chapter’s focused vision. The black-and-white captures are somber, gray, and low key — serious with a tinge of unshakeable melancholy. Three dimensional sculptures, a mirror, three dimensional flesh and blood, all flattened with extraordinary care into a photograph’s two dimensions. The unspoken fourth dimension feels like grief, or yearning, or their potent combination: an attempt (and inability) to reach across time to touch someone.

Benedetta Casagrande’s essay, “Molting, Molding, Mourning,” which closes the book, is a poignant meditation on photographic transformation and material. It confirms, with broad strokes, my initial suspicions as to the underlying loss at stake in the artist’s handiwork (pun, clearly intended). She writes: “Infamously mortifying in its precision, photographs proffer something akin to an insect’s molt: the shell of something that moments before was alive, and that, through shedding, suddenly becomes inanimate.” As the best essays do, it pulls everything together with succinct precision, offering enough of an explanation of the artist’s journey within the book to make me return to the images anew. In this understated and astonishing visual contemplation, there is an evocative mingling of joy and grief as we molt, we mold, and we mourn.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|