Deadbeat Club, Los Angeles, California, 2024. 80 pp., 11½x16¼".

I don’t know why photographer Gabriele Rossi called his new book with Deadbeat Club The Lizard, but I like to think it was named after Rango. In promoting the book, Deadbeat describes it as “a strange and uncanny atlas of the familiar transformed into the unfamiliar through the vision of a stranger who's only looking for some sort of home,” not unlike the story of the chameleon lost in the outskirts of Nevada. Rossi is Italian but came to the States to pursue a residency in New York City. He felt overwhelmed by the scale and cacophony of New York, such a stark contrast from his small village along the coast of Italy, and eventually he sought refuge by fleeing to the American West. An avid student of photographic history, Rossi approached the region thinking about Robert Adams and Timothy O’Sullivan, and used the dramatic vistas and mythologies of the West to reflect on the nature of home, his vision tempered by his feeling as an outsider in the United States.

|

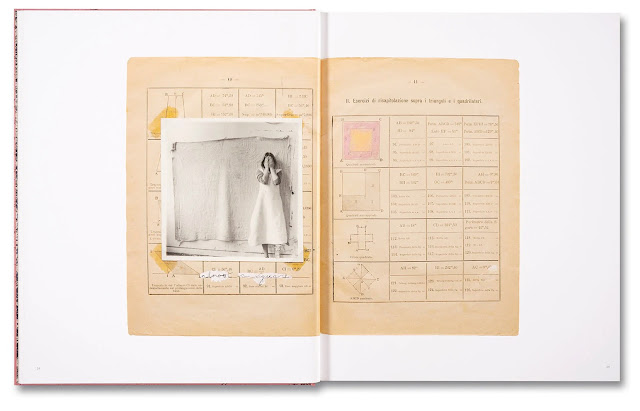

Everything about The Lizard is lovely. Measuring over 11x16 inches with the pictures printed one per spread, the book quickly seduces with large, rich duotone prints of familiar American landscapes. Rossi developed his pictures with a rigid formal and technical aptitude, beautifully articulated in the book as each page radiates light and clarity at the core of all his photographs. Perhaps most surprising here is his sense of humor. It’s not often I see landscape photography and grin, but I do so every time I open the book. I find this gives a refreshing view of the American West; Rossi does point out the successes and perils of Manifest Destiny, the political doctrine that dictated westward expansion, but he can see it as folly rather than tragedy. This is a subtle but important distinction, because it is easy to think that Rossi is repeating photographic histories of the American West. Artists like Emmet Gowin, Lewis Baltz, and Robert Adams thoroughly documented the tragedy, but Rossi accesses a sort of cleverness that I can only compare to Jason Fulford, perhaps best seen in the jagged white line he finds along the perfectly squared horizon, documenting a building that must host a business like the one Peter Gibbons experiences with Initech in the cult classic Office Space.

|

|

Deadbeat Club has been on my radar for some time — coffee and books are two of my favorite things in life — but this is the first of their books for me. I am interested in seeing more; The Lizard is clearly a book from a design team with great skills and perspectives on photographic narratives. With books from the likes of Vanessa Winship, Anne Rearick, and Toshio Shibata, Deadbeat is probing interesting and important photographic ideas about the connections between landscape and its manifestation in personal and cultural identity issues. Gabriele Rossi’s book fits perfectly into this vision by providing a familiar, engaging, and subtle approach to photographing the histories that help define the American West.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Brian Arnold is a photographer, writer, and translator based in Ithaca, NY. He has taught and exhibited his work around the world and published books, including A History of Photography in Indonesia, with Oxford University Press, Cornell University, Amsterdam University, and Afterhours Books. Brian is a two-time MacDowell Fellow and in 2014 received a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation/American Institute for Indonesian Studies.