|

Encampment, Wyoming. By Lora Webb Nichols.

|

Selections From The Lora Webb Nichols Archive 1899-1948

Fw:Books, 2020. 108 pp., black-and-white illustrations, 8¾x11".

Lora Webb Nichols was born in 1883 and died in 1962. For most of the years between (apart from a mid-life spree to Stockton, CA) she lived in Encampment, Wyoming, a small town on the eastern frontier of the Rockies. Webb was a devoted journal writer from pubescence until death. Beginning around 1899 (her camera a gift from the man she would marry) she was a prolific photographer too, first in an amateur capacity and later as a working pro. She founded her own studio, making commercial pictures as well as photo finishing, while always just barely keeping the creditors at bay. And, oh yes, she also supported two husbands and mothered six kids along the way. All in a day’s work.

Her photographic output totaled some 24,000 negatives, a massive quantity for the time. Nichols’ photographs and journals might be considered dual legacies of the same impulse, to affirm her presence by the power of careful observation. “I know I don’t amount to much,” she wrote disarmingly in her diary, “I don’t cut much figure. I can’t seem to do any good in the world… Nevertheless I’m here and will have to keep pegging away trying to make myself useful…”

|

Perseverance furthers. Today her archive is a treasure, providing both a detailed record of one person’s daily activities and a glimpse into early 20th-century frontier life. But Nichols’ photographs have another surprising dimension. Many transcend a mere functionary role, elevated into art by her uncommon camera talents. They would have been lost to history were it not for Nancy Anderson, a neighbor who befriended Nichols toward the end of her life and arranged to house her archive in what would become the Encampment Museum. They were a civic novelty but attracted little outside attention. Fast forward a half-century, when the Nichols photo archive was discovered in 2012 by Nicole Jean Hill. The archive was too unwieldy for the museum. It was poorly stored and disorganized. But Hill recognized seeds of promise. With Anderson’s help, she undertook a multi-year effort to digitize, organize, and curate Nichols’ photos.

|

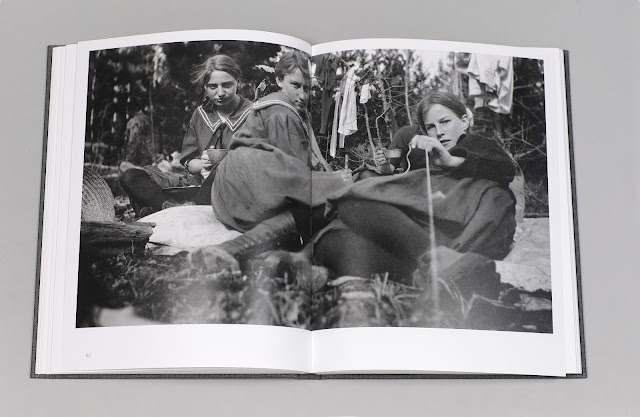

All three contributors — Nichols, Hill, and Gremmen — have joined forces to create a minor classic. That said, it is mostly Nichols’ show, as Hill and Gremmen wisely steer clear and let her photos take the lead. Frontier Wyoming comes alive before her camera, with a life force and casual aesthetic that feels quite contemporary. Gun-toting fur-lined grannies, fuzzy banjo players, hungry cats, balloons on Christmas trees. It all looks like a grand old time, and a weird one too. This is not the staid old west of C.S. Fly and Carleton Watkins, but one much closer to contemporary mores.

The book jumps into the photographs without a prelude. There are 115 in total, appearing in a range of sizes and layouts, one or two per spread. They bounce around in time and place. The reproductions are generally excellent. Scratches, hairs, and chemical artifacts of age have been cleaned up. Presented without theme or caption, the pictures have a time machine purity. The reader can sit on Nichols’ shoulder and encounter the world roughly as she saw. In addition to her photos there are some images by others included. These were gathered by Nichols as part of her collection, and they fit seamlessly into the mix although the authorship is separate. For those who want to sort photographers, dates, and locations, a helpful rear index lists that information, or at least what is known.

|

|

It’s worth lingering on the rear index a moment. It is one component of a sprawling text section that comes at the end as a design marvel. Nancy Anderson contributes an essay, followed by Hill’s story of discovery. Both women are openly enamored with Nichols, referring to her as “Lora” by first name. “I didn't want to initially include pictures that I wasn't confident were perfect in terms of both form and content,” explains Hill, “or could be labelled as a collection of snapshots, because I really wanted to the photo world especially to take Lora seriously as a photographer.” A plate listing and brief bios close out the writing. Several photographs are inserted in the essays, including a few of Nichols herself. The entire section is printed on silver ink against black matte paper, an abrupt departure from the white polish of the main body. The photographs shimmer with a ghostly glow, and even the words seem photographic in their vibrancy. One almost wishes the entire book could be this way. Almost. On second thought it’s fine as-is.

The photo world has experienced a tidal wave of similar projects in recent years, as contemporary photographers and curators mine and reappropriate old film archives in new ways. Compared to most, this one offers a relatively unfiltered channel to a bygone era. The design is dowdy, with a grey clothbound cover and plain san-serif typeface. The main body’s division into white paged photographs and black matte text section shows a flared reserve. The structure is conservative, functional without taking centerstage. The reader’s attention is directed to Nichols and her extraordinary legacy.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.