|

There will be two of you by Michael Ashkin.

|

Photographs by Michael Ashkin

Fw: Books, 2023. 208 pp., 9½x11".

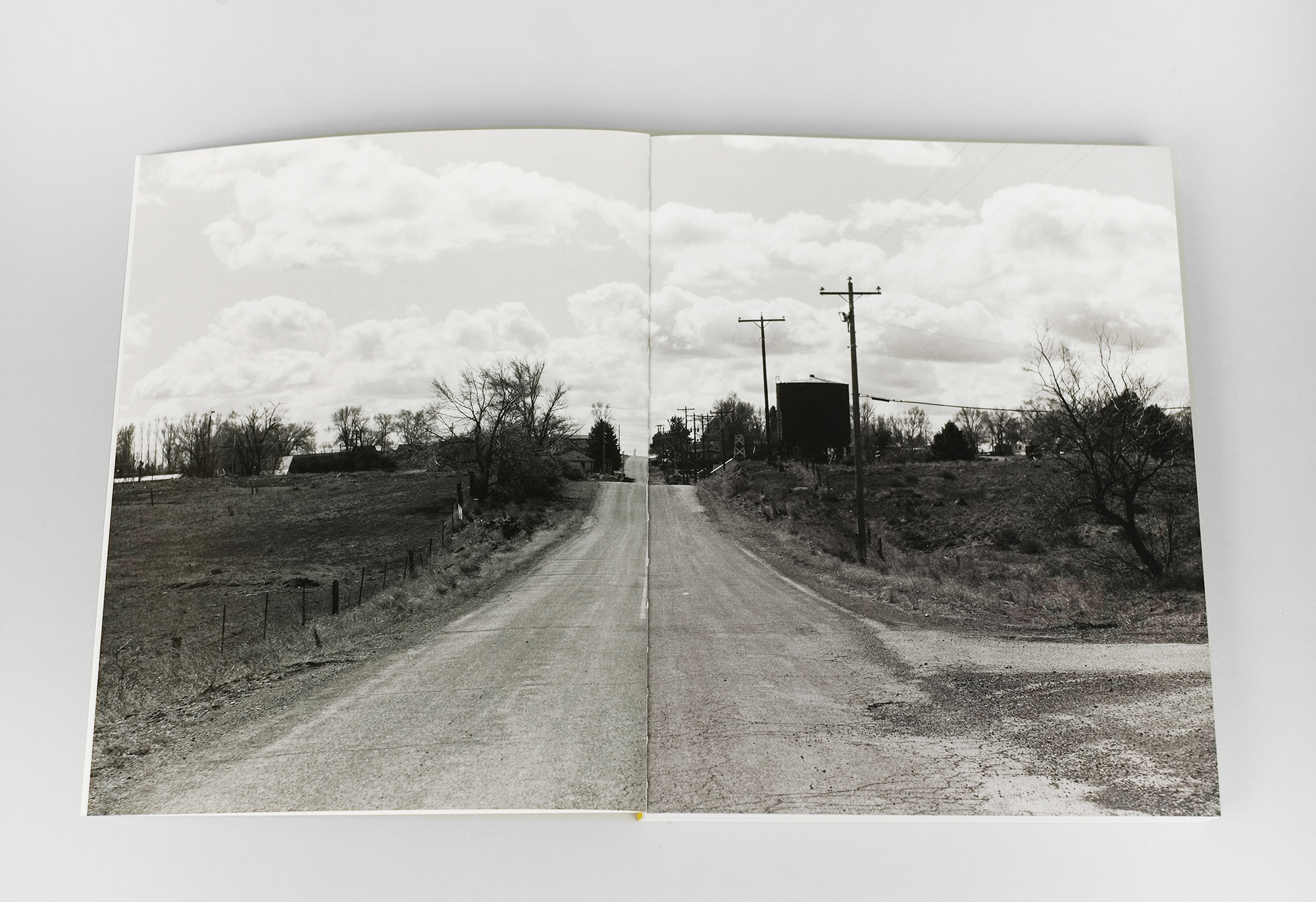

The New Jersey Meadowlands — a swampy territory accommodating the landfills, junkyards, processing plants, and factories necessary to upkeep Manhattan’s world of appearances — are frustrating to traverse if you’re late to Newark Airport, but fascinating as evidence of capitalism’s environmental impact. Their increasing geographical precarity can be summarized by the fact that some of its neighborhoods are still recovering from Hurricane Sandy more than a decade later. Far from picturesque, most avoid the meadowlands if possible. The artist Michael Ashkin experienced this landscape from a young age, developing an unexpected empathy toward it. That he witnessed it mainly through the car window might explain how he would later come to render it visually. Ashkin’s photobook There Will Be Two of You confronts us with spaces in the meadowlands that might seem purposeless or devalued but have a long history of exploitation by the array of colonizers, governments, corporations, and mafias that have ruled the Garden State.

The area depicted looks like a real-life maze with no landmarks or prominent points of reference. According to Ashkin, his first pictures of the meadowlands didn’t reveal anything, pushing him to experiment with several formats and styles before finding a methodology that reflected its intricacies. He adopted the panoramic format because he felt it resonated with his experience of the landscape. One of my undergrad lecturers, Craig Stevens, loved to say that all great photographers eventually use the panoramic format. Beyond debatable definitions of greatness in photography, I take Stevens’ dictum to mean that the artist’s choice of tools to render their subject matter can make or break the images they produce.

|

|

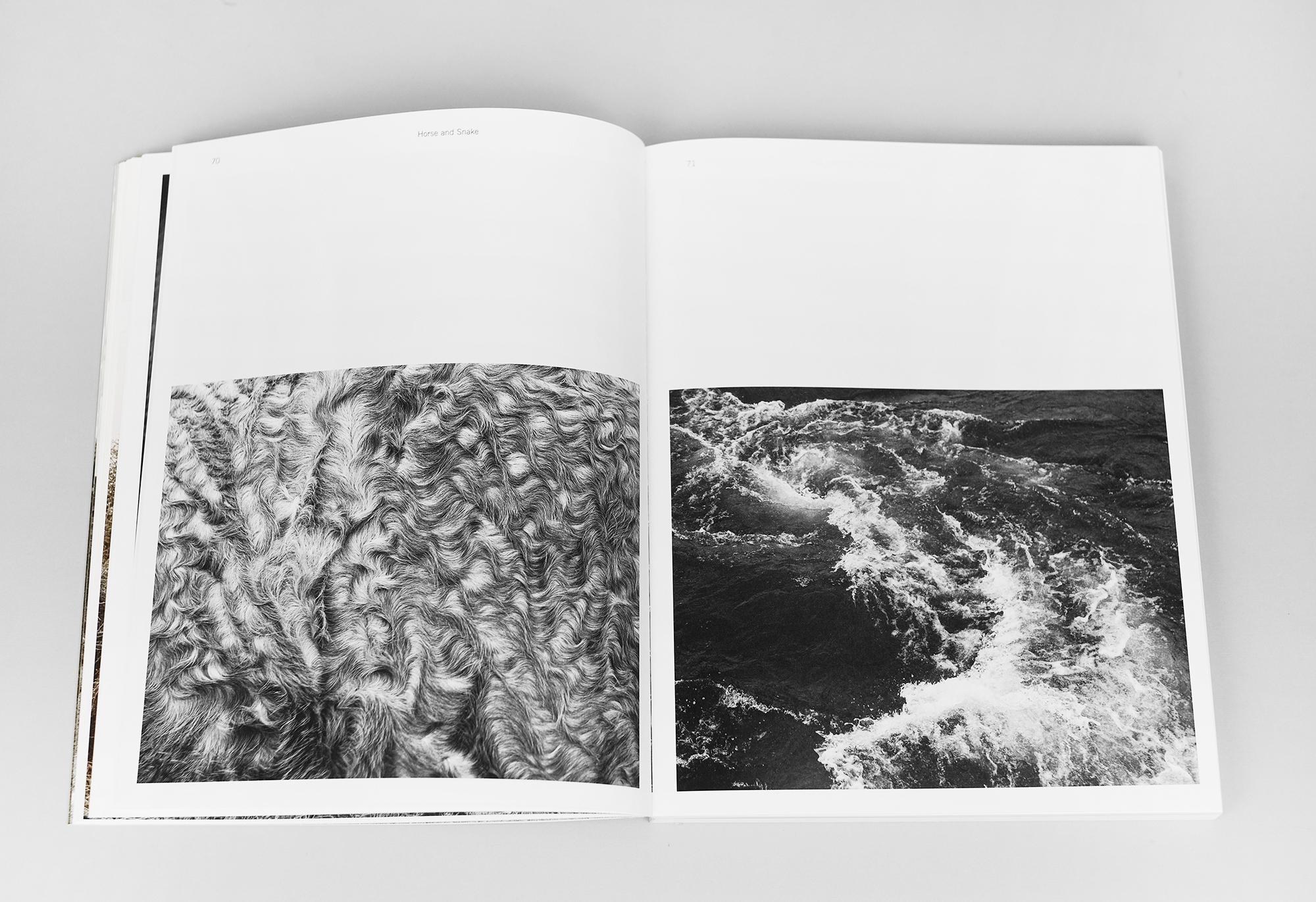

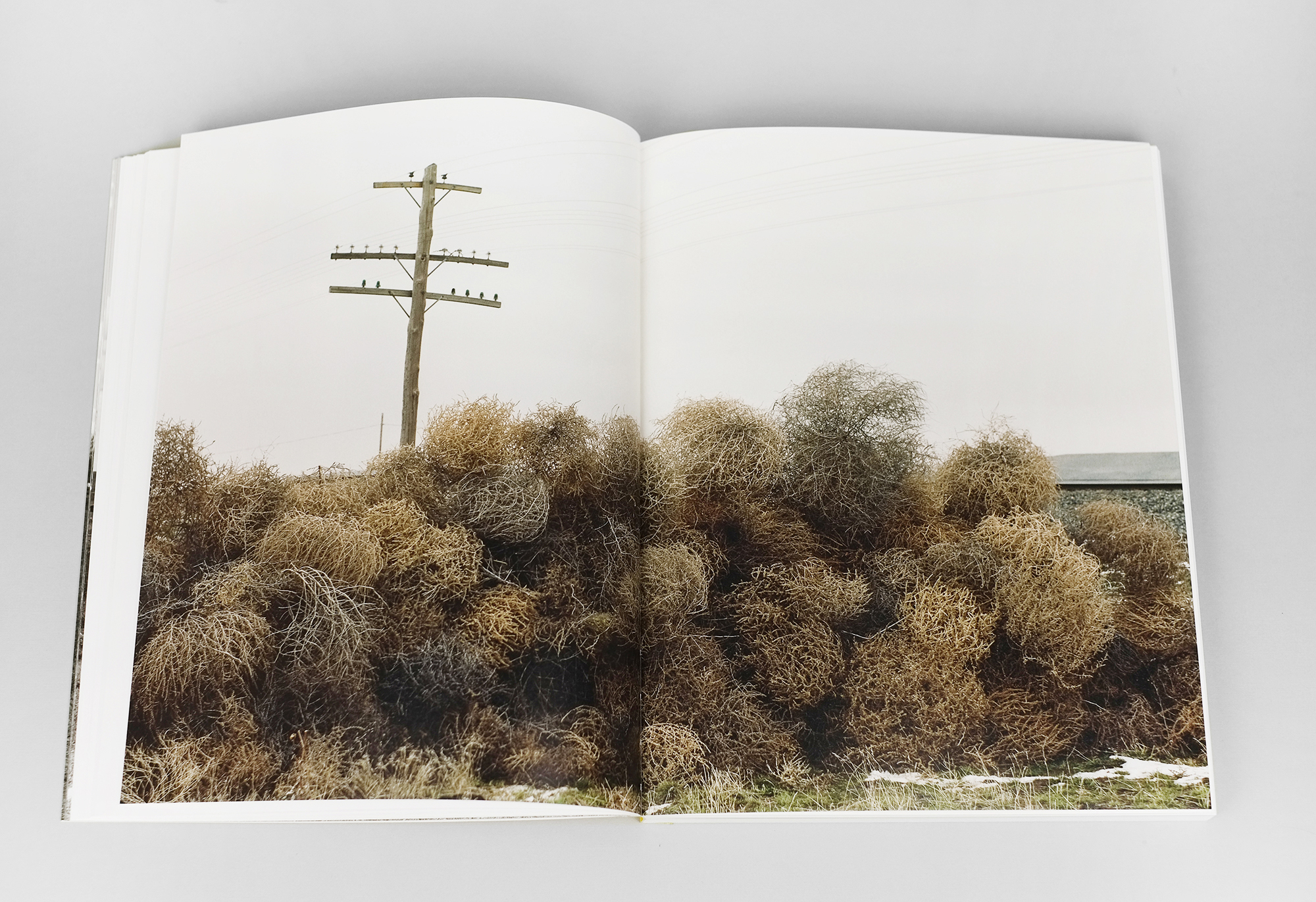

Applying the panoramic format to still images is challenging because it creates a nearly unavoidable sense of unity, making things appear as if they naturally fell into place within the frame. The more elongated the rectangle, the harder it becomes to find variations that break up the pictorial space — a problem that cinema resolves by moving the camera, the subjects, or both. As such, the marked impression of chaos that the pictures in There Will Be Two of You give is unusual. Ashkin’s varied compositional strategies underline his effort to resist the aesthetic constraints of the format and the grittiness of the terrain in a constant flow between the raw and the cooked that is integral to his work (and the primary source of this book’s vitality).

|

In an interview, Ashkin described trespassing as a cheap thrill he enjoyed, which tells of his complex relationship with some of these spaces and hints at the difficulties behind making the pictures. It’s possible to imagine Ashkin being chased by a dog or a gatekeeper, confused about why someone would want to photograph a pile of tires (this has to be the book with the most tires and containers in it). While we will never know which ones were dangerous to make, the pictures collectively describe the desolation of a postindustrial landscape affected by the whims of a rapidly changing world. Unlike other series about suburban wastelands that overplay the pictorial transformation of ruin into beauty, There Will Be Two of You forges an organic link between these unspectacular spaces and the style utilized to subvert our assumptions of them. The density of information in these pictures is peculiar, given that most people think of this area as empty. The contradictions between what we think we see and what is actually there have long been of interest to Ashkin, particularly how our point of view determines the ways we apprehend ordinary spaces. He has often explored this aspect in his sculptural works, big architectural maquettes that replicate non-places such as parking lots or highways.

|

|

In a story at the end of the book, an unnamed narrator tells — in the second person singular — how two people break into an abandoned complex and have a transcendental experience when they see a beam of light creeping into a building. This grammatical tense can cause a feeling of dislocation when used narratively. Here, it insinuates our failure to communicate the significance of sensory experiences with words: “You will sense the insufficiency of your description. You will expand on it without satisfaction. Your language will reveal a crisis of scale. Your language will separate itself from you. You will have lost the event.” Something similar happens with the pictures. They are the outcome of an immense physical effort, but they cannot encompass the complexity of a territory that is haunting because of its apparent dullness. The text made me think of the pictures differently, more psychologically, as the work of someone who wanted to be alone but was also sickened by the solitude of the landscape in front of him.

|

The overall purpose of the text is vague, ringing like an indeterminate allegory that nevertheless resonates with the book’s title to suggest a few possible doublings. Firstly, as an homage to the other explorer, the friend who often accompanied Ashkin on many outings. Then there is the potential mirroring of the author in time, as if the making of the book confronted Ashkin with his former self that made the pictures (perhaps inevitable when revisiting one’s archive). Yet another way of reading the title is through the eternal rivalry between the twin states of New Jersey and New York, and how the fate of one directly influences the other.

It’s not easy to make a book exclusively with panoramic pictures. When such collections get published, the books tend to be large, horizontal, and with too many foldouts. Hans Gremmen, the designer of FW Books, found ingenious solutions to avert those characteristics. The pictures in most spreads are small, up to three to a page, but in varying configurations. Every so often, a picture is split into three full-page sections, meaning you can only see the whole of it by turning the page. This arrangement begins at the cover, printed on a blue stock that looks like a folder you might encounter in a real estate agency or government office conducting a land use survey.

|

Despite the archival insinuations of the cover, these pictures come with a consummate pedigree: the esteemed curator Okwui Enwezor commissioned the series for Documenta 11 in 2002. It is strange how current the book feels, given the pictures were made more than twenty years ago. While certain kinds of urban devastation might appear timeless, the book’s traction has to do with the attributes of the photographs and the way its design exploits their graphic magnetism. As in Ashkin’s previous books, there is much visual pleasure to be found here, even if it doesn’t materialize conventionally. I always get a strong feeling of singularity whenever I engage with his books, like listening to someone explaining things distinctively, structuring their argument in a way that makes you appreciate the mental choreography required to reach a conclusion that, through their punctual use of rhetoric, feels not only convincing but also immensely gratifying.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Arturo Soto is a Mexican photographer and writer. He has published the photobooks In the Heat (2018) and A Certain Logic of Expectations (2021). Soto holds a PhD in Fine Art from the University of Oxford, and postgraduate degrees in photography and art history from the School of Visual Arts in New York and University College London.