|

By Graciela Iturbide.

|

Photographs by Graciela Iturbide

Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, 2022. 304 pp., 250 illustrations, 9¼x11½".

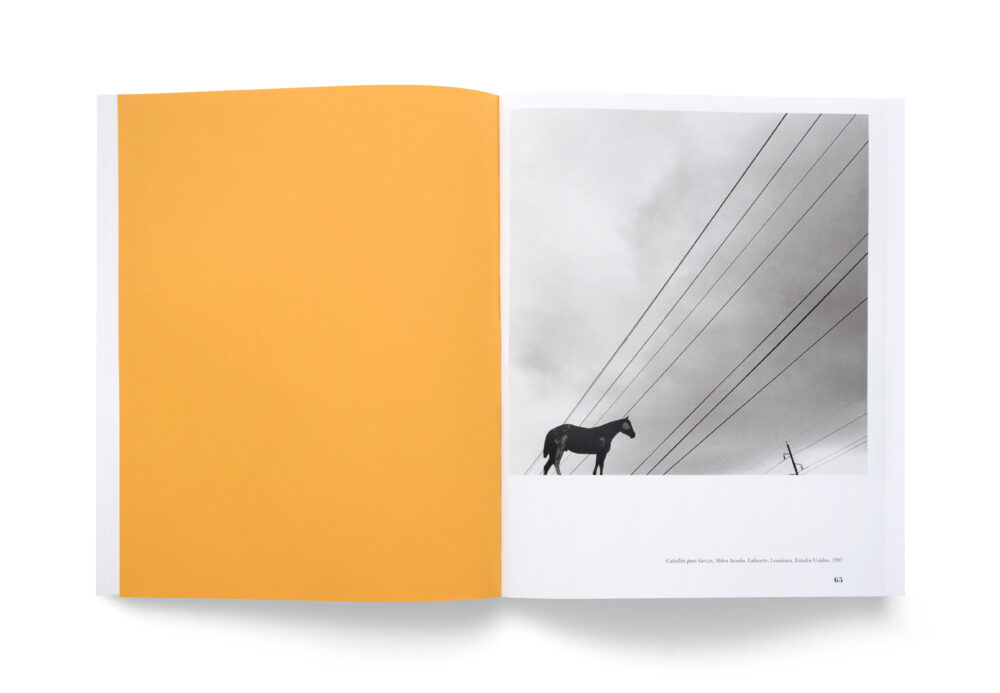

Organized by the Fondacion Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Heliotropo 37 presents an overview of Graciela Iturbide’s prolific career. The book catalogs her best-known projects including Los Que Viven en la Arena (Those Who Live in the Sand), a series of the Indigenous Seri people living in the Sonora Desert; Juchitán (The Women of Juchitán), which focuses on the female-centered Zapotec culture of Oaxaca; and Naturata (Nature), photographs of Jardín Botánica de Oaxaca. In addition, the Fondacion commissioned a series of photographs produced in Tecali, a village close to Puebla in Mexico. In a departure from her signature black-and-white, Iturbide photographed alabaster and onyx slabs in color during the process of mining and polishing the stones. The images of these immense forms, strangely poised between the organic and the man-made, act as an introduction. Heliotropo 37 takes its title from her studio address in Mexico City, a structure designed by her son, the architect Mauricio Rocha. Photographed by Pablo López Luz, the building is an adamantly private space; its edifice is constructed of solid brick and its interiors blend the domestic with the trappings of a studio. It’s fitting that this survey is housed within a structure that reads as a character study, a portrait in absentia.

|

The book is ostensibly organized in sections that represent these distinct projects, yet its editing departs from partitioning of subject to generously alight into the shared spaces between. As such, two distinct pulls structure the book’s sequencing — the desire to bestow order to her catalog and to find an editorial form for her searching gaze; a rebellious and welcome impulse against the chronological. Iturbide is attuned to cultural detail — there’s an anthropological tug to her work — but her gaze seeks the ineffable.

Birds glide through Iturbide’s photographs, an animating line through the book — swarming, swooping, floating, piercing the sky. In Pájaros (Nueva Delhi, India, 1998), a man with a bandaged head and cane in hand walks through a trash-strewn landscape. He is dwarfed by a swarm hovering over him, like a crowded thought bubble. Three birds fly triangulated over a group of four, earth-bound dogs (three with question mark tails!) in Perros perdidos (Rajastán, India, 1998), fusing earth and sky, substance and shadow. In a pair of images, Pájaros en el poste de luz and Árbol de pájaros (Both Carretera a Guanajuato, México, 1990), clouds of birds bloom over a telephone line and tree respectively, as if born from these other forms.

|

|

These aerial silhouettes connect to another enduring theme, the shroud and the mask, summoning Iturbide’s preoccupation with mortality. She moves easily between documentation, as seen in the recurring imagery of Day of the Dead masks and their ritual uses, to veiling as a figurative strategy. Even objects receive this melancholic attention: a sedan covered in a flowered bedsheet, a block of ice draped in a dark towel, the cacti of Jardín Botánica swathed in newspaper. This strategy takes its most dramatic form in her use of animals as masks. ¿Ojos para volar? (Coyoacán, México, 1991) shows Iturbide’s head reclined back, positioning two birds whose heads align with her eyes. The head of the bird on the right optically fuses with her eye in a gesture of blinding, its skull shadows as an empty socket. In another self-portrait, she holds a small fish over her mouth, pulling it close to the contour of her face, as she looks off-camera. (Pachuca, México, 1995)

In an interview with TK, Iturbide says: “Everything in life is connected: your pain and your imagination, which can help you forget reality. What you are living is connected to what you dream about, and what you dream about is connected to what you do, and photographs remain lasting reminders of this.” Iturbide’s capacious gaze offers matter and metaphor, seeing the mythological in the detail of experience and Heliotropo 37 gives flight to her grounded and spiritual sensibility.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Laura Larson is a photographer, writer, and teacher based in Columbus, OH. She's exhibited her work extensively, at such venues as Art in General, Bronx Museum of the Arts, Centre Pompidou, Columbus Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, SFCamerawork, and Wexner Center for the Arts and is held in the collections of Allen Memorial Art Museum, Deutsche Bank, Margulies Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Microsoft, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, New York Public Library, and Whitney Museum of American Art. Hidden Mother (Saint Lucy Books, 2017), her first book, was shortlisted for the Aperture-Paris Photo First Photo Book Prize. Larson is currently at work on a new book, City of Incurable Women (forthcoming from Saint Lucy Books) and a collaborative book with writer Christine Hume, All the Women I Know.